Cozumel, Texas

Cozumel, Texas

Copyright 2011, Ric Hajovsky

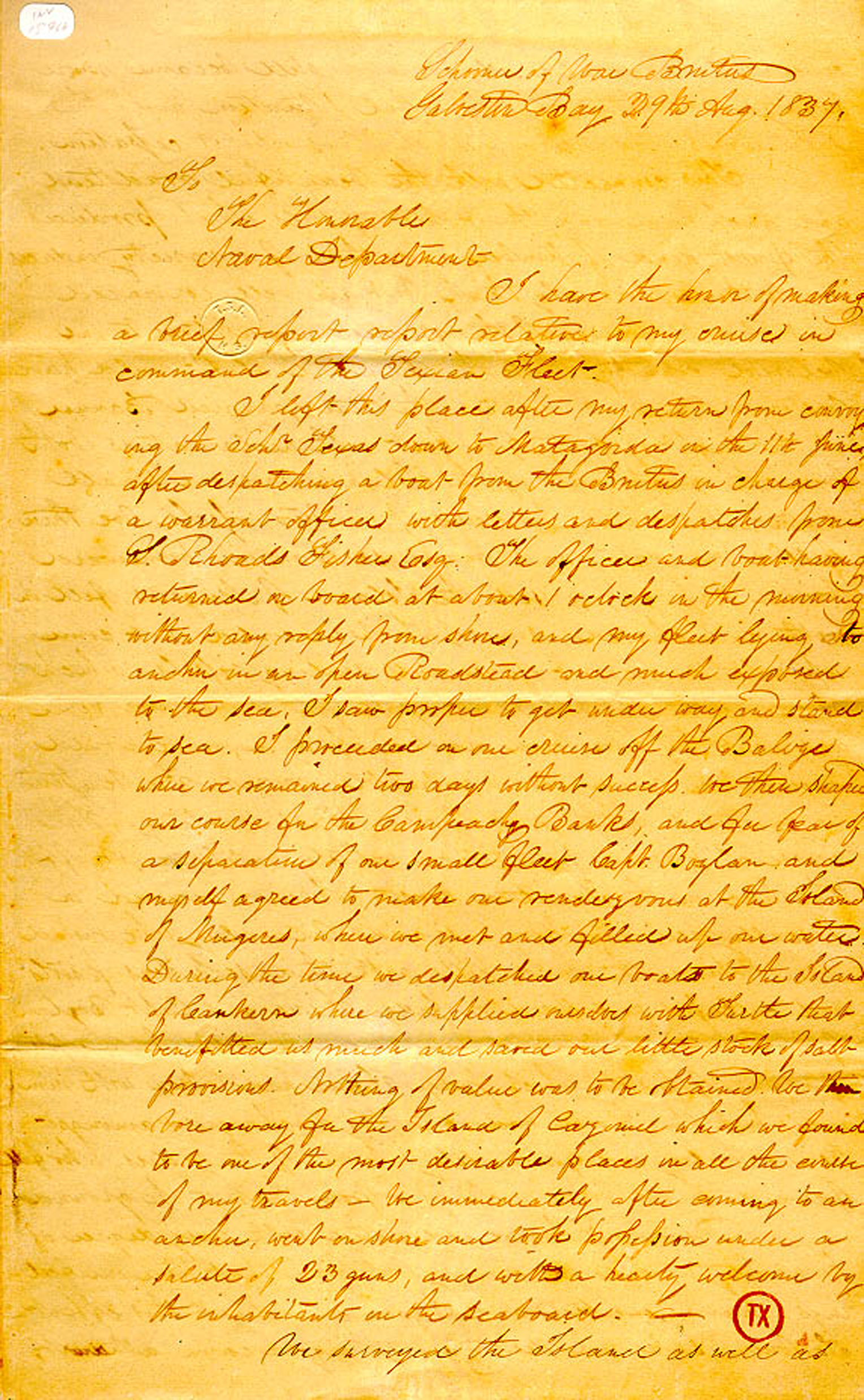

In June 1837, one year after the Republic of Texas became independent from Mexico, the Texas Secretary of the Navy, Samuel Rhoades Fisher, sent the two Texas Navy Schooners of War (the Brutus and the Invincible) to the coast of Yucatan to harass Mexican shipping in retaliation for Mexican blockade of Texas ports. This was against the express wishes of the President of Texas, Sam Houston. After raiding several Yucatecan towns and capturing several Mexican vessels, the Texan fleet sent a landing party ashore at Cozumel and claimed the island formally for the Republic of Texas. The Texian Navy Commander Henry Livingston Thompson of the Brutus sent a dispatch on August 29, 1837, to his headquarters in Galveston regarding this foray, containing the following lines:

“We then bore away for the Island of Cazomel which we found to be one of the most desirable places in all the circle of my travels. We immediately after coming to an anchor went on shore and took possession under a salute of 23 guns and with a hearty welcome by the inhabitants on the seaboard. We surveyed the Island as well as circumstances would admit and still became more infatuated with its delightful situation and the salubrious trade wind which blows without cessation. This connected with the beautiful roadstead and anchorage and the richest of soils which produces the finest kind of timber and that of a variety induces me to think, not only think but am well convinced that it will be one of the greatest acquisitions to our beloved country that the Admiral aloft could have bestowed on us. I hoisted the Star spangled Banner at the height of forty-five feet with acclamations both from the inhabitants of the Island and our small patriotic band, the crews of our two vessels. We then filled our water and made sail on our homeward bound passage, passed the Island of Mujeres.”

Above: The report H. L. Thompson made, telling of how he claimed Cozumel for the new nation of Texas in 1837.

After Fisher and Thompson submitted their reports of the voyage, they were reprimanded for their actions by the President of Texas, who did not want to upset the status quo with Mexico by claiming part of its territory. Sam Houston then fired the Texas Secretary of the Navy, Samuel Rhoades Fisher, for disobeying orders. Thompson was brought up on charges but died before the trial.

Eleven years later, in 1848, the governor of the independent Republic of Yucatan was losing the War of the Castes to the Maya rebels. As a last desperate measure, the governor of the Republic of Yucatan offered the entire territory to the United States in return for putting down the rebellion but the offer was turned down.