How Cozumel was formed and first Populated

How Cozumel was Formed and First Populated

Copyright 2016, Ric Hajovsky

The bedrock that lies beneath Cozumel and the Yucatan peninsula is made up of a sequence of shallow-water limestone, some 1,300 meters thick that was deposited between 200 million and 145 million years ago, during the Jurassic Period. This first layer of limestone was later overlain with a second 1,000-meter-thick layer of calcareous marine deposits during the Cretaceous. Still later, another 15 meters was deposited during the Miocene and Pliocene.

Around 66 million years ago, at the same time as the Chicxulub impact, a Horst block was squeezed upwards from between two fault lines running parallel to the east coast of Quintana Roo. Although the upper surface of this block remained below sea level at the time it was extruded, later sea level fluctuations exposed the block and it became what we now call Cozumel Island.

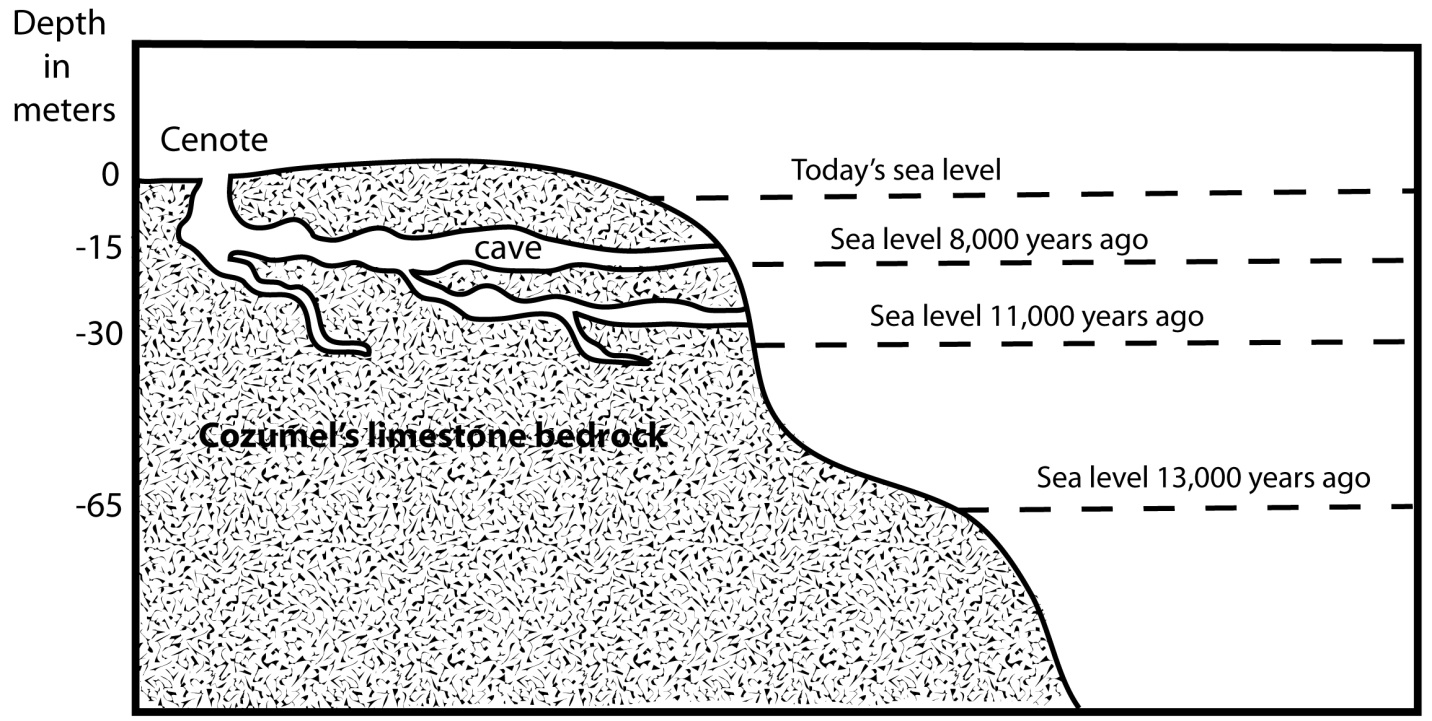

During the Pleistocene, the sea level alternately rose and fell, depending on the amount of the Earth’s water that was sequestered in the glaciers that covered most of Northern America, Europe, Asia and the southern parts of South America and Africa. Twice during this period, the sea level dropped to around 65 meters lower than it is today. That put the surface of Cozumel and the adjacent Quintana Roo coast around 75 meters above sea-level during those ice ages. Throughout the Pleistocene, the rainwater that fell on the Yucatan peninsula and Cozumel percolated through the exposed, porous limestone, dissolving cracks and fissures that enlarged over millennia into deep caves and caverns.

Above: Chart showing the sea level rise over the last 13,000 years on Cozumel.

Later, during the Pliocene, the ice sheets retreated and the sea-level rose, flooding these dry caves and turning them into the water-filled anchialine caves and cenotes we have today. Recently, cave divers have been discovering the skeletal remains of extinct Pleistocene fauna (Saber-toothed tigers, New World horses and camels, and mammoths, among many others) in these now-flooded Yucatecan caves and caverns, as well as early human skeletal remains. In 2001, German Yañez found several bones from the extinct North American horse, Equus conversidens, in the Sifa cenote near Chankanaab Park.

The question often arises, “When was Cozumel first inhabited?” So far, no archaeological evidence has been uncovered that could firmly establish a date earlier than the Pre-classic (or Middle Formative period) some 3,000 years ago. However, there is no reason to discount the possibility that small groups of the Paleo-Indians who had been migrating south from the Bering Strait may have visited Cozumel or even established themselves temporarily as early as 14,000 years ago. Remains of these early New-World colonizers are just now beginning to turn up in the deep cenotes of Quintana Roo. The skeletal remains of the Paleo-Indian “Eve of Naharon” that was recently discovered in the Naranjal cave system near Tulum has been carbon-14 dated to 11,600 B.C., over 13,600 years ago. The 10,000-year-old remains of the Paleo-Indian “Mujer de La Palma” and the child “Joven de Chan Hol” that were found near Tulum in Las Palmas cenote and Chan Hol cenote are just a few of the other finds that have pushed back the timeline for the population of Quintana Roo.

These Paleo-Indians were only the forerunners of the human migration southward in the Americas. By 8,000 years ago, Archaic period hunter and gatherers had populated Yucatán. Shortly thereafter, groups of these early settlers migrated out from northern Quintana Roo to settle the western portion of the Antilles and become the Casimiroid culture in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola and other Antillean islands.

Around 4,500 years ago, during the Early Preclassic period (also known as the Early Formative period), the very beginnings of the Maya civilization began to coalesce and become what we now call the Proto-Maya. Within a few hundred years, these Proto-Maya begin to farm corn and their settlements become more permanent in nature. By 1000 B. C., or 3,000 years ago, the Maya culture had evolved into what we now call the Middle Preclassic or Middle Formative period. The earliest dateable artifacts on Cozumel are from this period.