COZUMEL AND THE SLAVE TRADE

Copyright 2011 Ric Hajovsky

The frequently heard statement that Cozumel was abandoned in the 1700s due to predations by bands of roving pirates is nearly true. The island was an easy target for buccaneers and in the mid-1600s the Spanish government finally decided to move the population inland, to towns like Chemax and Xcan Boloná that were far from the marauders’ reach. Some Cozumelenos did, in fact, move to the mainland. However, many stayed on the island and were joined by English dyewood cutters, later known as “piratas.”

Miguel Molas called Cozumel home in 1828, but after he moved away in 1830, a partnership from Merida began a cotton plantation near his old rancho on Cozumel with some 30 convicts from Merida’s prison providing the slave labor. This plantation continued to work until 1841.

Beginning in 1847, during the war of the Castes in Yucatan, more people began to drift back to the island. Seeking a safe refuge from the Mayan rebels that were intent on purging the peninsula of all the Spanish and mixed-blood newcomers, several groups of creoles, mestizos, foreigners, and their Mayan servants soon set up households on Cozumel. They initially found the island a hard place to make a living, but soon enough found a revenue producing commodity; captured Mayan rebels they could sell to the Cubans a slaves.

Just how did the island’s population turn from pirate prey to predatory slave traders? The demographics changed. Prior to the Spanish government’s forced resettlement of many of the island’s residents between the years 1650 and 1688, the typical Cozumeleño was a full-blooded Maya Indian. Although the institution of slavery was integral to Maya civilization, the Yucatecan Maya civil organization had undergone immense changes after surrendering to the Montejos and their Spanish soldiers. By the mid-1500s, the Yucatecan Maya were nothing more than the Spaniards’ subjugated labor force and no longer had the power to capture and keep slaves themselves. However, the majority of the later inhabitants of Cozumel, beginning with the fugitive contrabandista and slave trader Miguel Molas in 1828, were either Spanish, creole, or mestizo. They had grown accustomed to the fact that they were the beneficiaries of the trade in human flesh and not the target. Although Mexico abolished slavery in 1829, it was not made illegal in Cuba until 1862. This made it very tempting for the Repobladores who fled to the island to avoid the war on the mainland to take advantage of their distance from the government authorities in Merida and dabble in the trade whenever the chance presented itself. Judging by the few records that still exist, the occasion presented itself pretty frequently.

On November 21, 1849, the government of Yucatan officially recognized the town founded by the group of refugees who settled on Molas’ old rancho as the “Pueblo de San Miguel de Cozumel” and linked it to the municipal government of Tizimín. That same day, José Francisco Rosel, aged 62 and one of the new immigrants from Xcan, was named the island’s first alcalde. The following January, a census was taken of the residents of the island, which counted 307 adults and an unspecified number of children under 12. Of these adults, 9 were from countries other than Mexico: 2 from Cuba, 1 from Spain, 1 from Guatemala, 2 from the US, 1 from Italy, and 1 from Africa. Only 99 of these repobladores were Maya.

In early 1849, Alcalde Rosel submitted a report to the Yucatecan government detailing the number of vessels arriving at Cozumel, along with their cargos and the names of their masters. For the month of January of 1849, the report tallied 10 vessels; 1 American, 1 English, 5 Belizean, and 3 Mexican. Were these all the vessels that called on the port? Definitely not. It seems there was a lively illicit slave-trade going on between Yucatan and Cuba that was using Cozumel and Isla Mujeres as transshipment points and most of these clandestine voyages went unrecorded. A few of these slaving trips, however, did leave behind a record of their deeds. For example, on December 21, 1850, it was recorded by the Captain of the Port of Cozumel that the Cuban vessel Alerta, captained by Francisco Martinez, arrived in Cozumel with an empty hold. This vessel was one of the many that belonged to the Cuban slave-trader Francisco Martí y Torrens, also known in Cuba as Pancho Marti. Pancho Marti held a special concession to fish in Yucatan waters, granted to him by the Yucatecan government. This cover operation was just one of many he used to disguise his slave-trading enterprise that operated in Cuba, Yucatan, the American Gulf Coast, and Africa. It is a pretty safe bet that when Pancho Marti’s boat left Cozumel for the trip back to Cuba, its hold was no longer empty.

Often the facts of a slaver’s voyage were recorded only because of some unforeseen event, as in the case of the 35-foot-long sailing vessel Sol, captained by Feliciano Peraza. It was the same boat that had carried John Lloyd Stevens and Frederic Catherwood to Cozumel 11 years earlier. The Sol sank on May 10, 1852, with a cargo of 9 slaves (described as “servants” in the report of the wrecking event made by Enrique Angulo, the second Alcalde of Cozumel) belonging to a Juan Bautista Anduce. Two of the slaves drowned, but seven made it safely to the shore and freedom. Peraza managed to raise the Sol and he had repaired the vessel by that June, when he returned to Rio Lagartos to pick up more “servants” for Sr. Anduce. After rounding up another group of Maya and securing them aboard, the Sol anchored at Punta Francés in Holbox for the night. The captured Maya took advantage of the stop-over, breaking their bonds, killing Peraza and severely wounding his two deckhands, Pantaléon Rosado and José Carrillo. Rosado was able to sail the boat to Isla Mujeres, where a posse was assembled and sent out to recapture the escaped “servants.”

In June, 1852, another boat lost four “servants” who had escaped when that boat also stopped overnight at Holbox on the way to Cozumel. This same month, the Petrona, captained by Guadalupe Pech, carried 13 Maya to Cozumel consigned to Colonel José Dolores Cetina. A few days later, Manuel Gascas’ Joaquina out of Telchac, struck a reef off Cozumel and sank with an unspecified number of “servants” aboard consigned to Tómas Mendiburu, the owner of a rancho on Cozumel. Before the month was out, the Segunda Antonia, captained by Casiano Cosgaya and out of Sisal, docked at Cozumel with a cargo of 17 Mayans who Pilar Canto shipped to the island from Mérida.

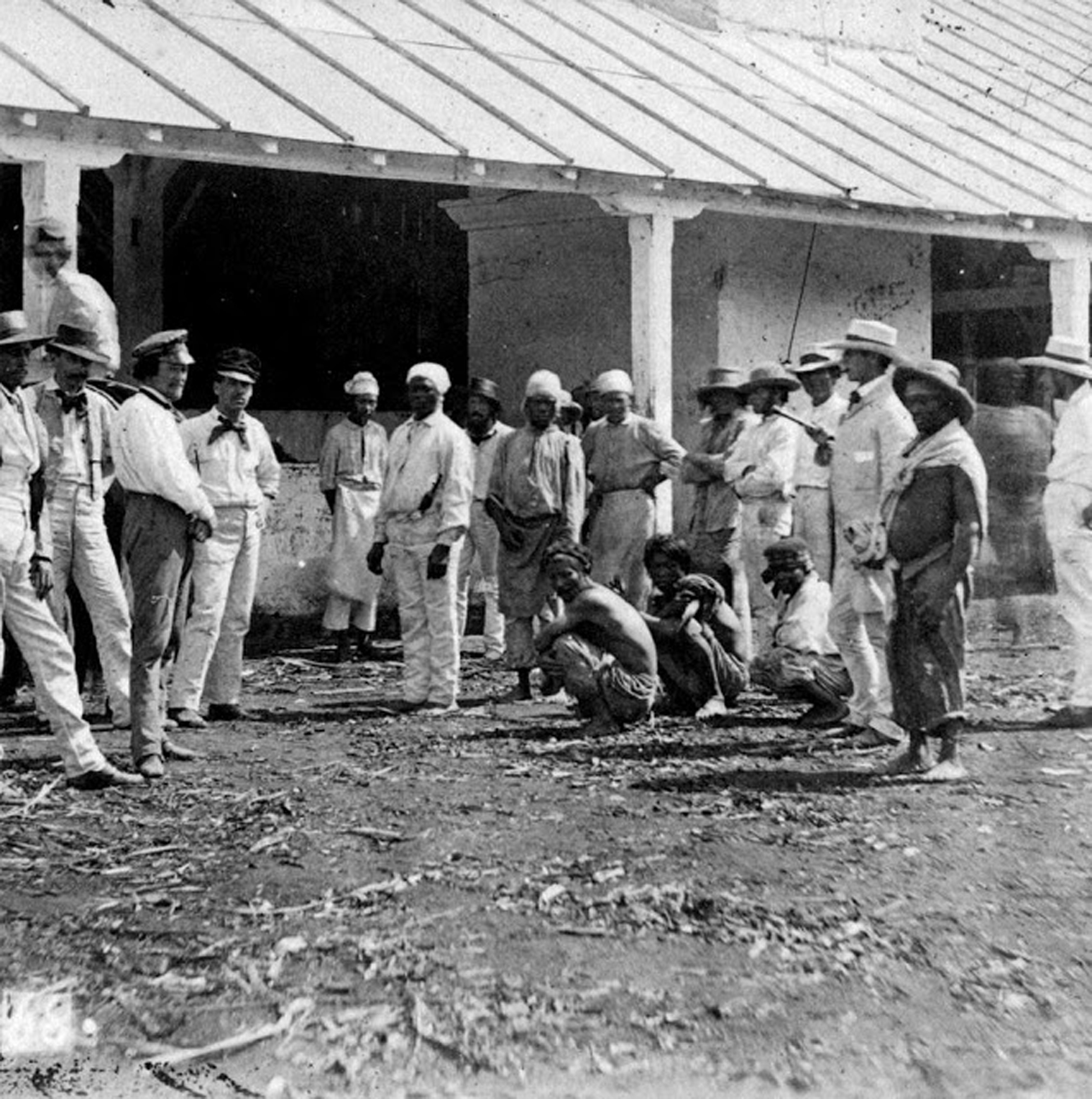

Above: Young Maya slaves working the sugarcane fields in Cuba

What percentage of the slave trade these few reports represent is unknown, but it is most likely a very small one. The route was well established. The Maya captured in Yucatan were taken first overland to Rio Lagartos and then to Cozumel and Isla Mujeres by sailing vessel. There, the slaves would be held while the slave-traders awaited Cuban “fishing” boats to come to the islands and purchase them. The slaves would then be taken to Cuba inside the fishing boats’ viveros or “live pens” and sold to sugarcane plantation owners.

Not all slave traders got away clean. Juan Bautista Anduce was eventually arrested in Belize by British authorities and was sentenced to four years in prison for shanghaiing Maya rebels near Bahia Asuncion and taking them to Isla Mujeres aboard the vessel Jenny Lind, where they were transferred to a Cuban vessel sent by Anduce’s contact in Havana, Francisco Martí y Torrens. When Anduce was arrested, he still had a letter in his pocket from Martí y Torrens, outlining the deal: 25 dollars for each adult male, 17 dollars for adult females and adolescent males, and eight dollars each for boys under 12 and girls under 16.

Above: Maya slaves being delivered by a ship’s captain to a Cuban plantation owner.

Juan Bautista Anduce was not the only person that we know about who dealt with Martí y Torrens. Luis Luján, former resident of Isla Mujeres and manager of Ranco Santa María in Cedral, had a large stable of “servants” working rancho Santa María and also owned the vessel Josefa, which he used in several dealings with the Cuban slave trader.

Above: Francisco Martí y Torrens, the Cuban slave trader.