“Eagle on the Cactus Eating a Snake” Myth

The Raptor in the Mexican Coat of Arms should not be an Eagle nor have a Snake in its Talons

Copyright Ric Hajovsly, 2016

Do you know the origin of the image of the eagle perched on a cactus and holding a snake in its talons? It comes from a myth on the origins of the Aztec people. However, in the myth, the eagle was a falcon and it was not holding a snake!

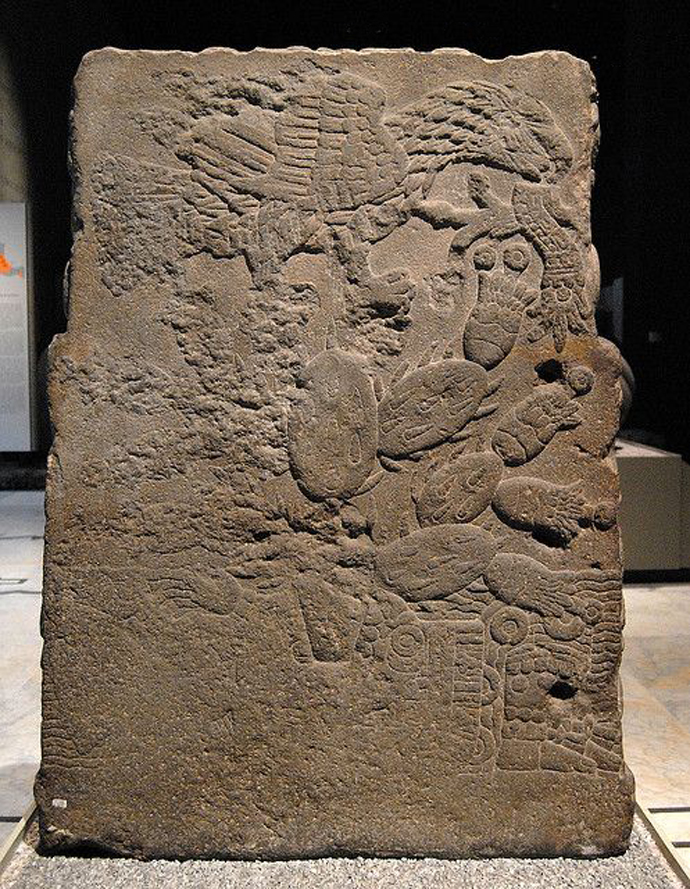

Below is the Teocali de la Guerra Sagrada (or, “Holy Temple of the Sacred War”), a throne in the shape of an Aztec temple. It was discovered in Mexico City in 1926 buried under the National Palace. According to the glyphs carved into its surface, it was made by the Aztecs in 1507, 12 years before the arrival of Hernán Cortes.

Below is the back of the throne. It has a design in bas-relief of an eagle perched on a nopal cactus with an atl-tlachinolli near its beak. The atl-tlachinolli is a compound glyph, made up of two signs: atl (“water” in Náhuatl) and tlachinolli (“burnt land” in Náhuatl), and is a metaphor for “war” in the Aztec language. It is also a euphemism for blood, something very sacred in the early Mexican cultures. This compound glyph has nothing to do with snakes.

This throne is the oldest existing representation of the myth describing the founding of Tenochtitlan, which was later renamed Mexico City.

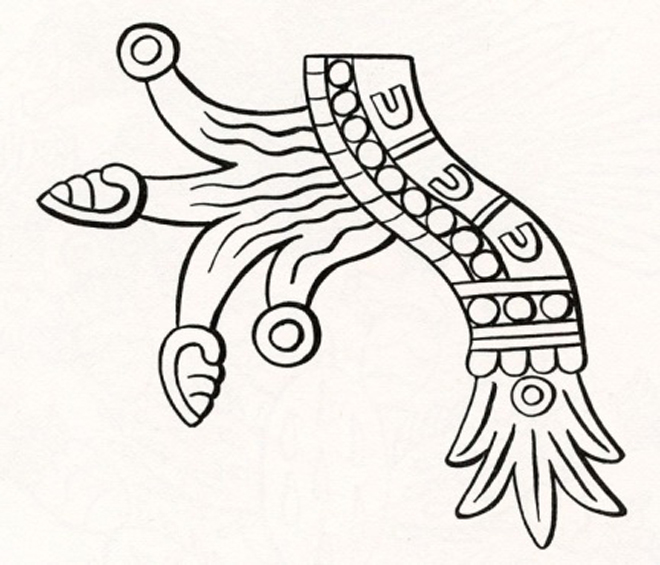

Above is an amplification of the atl-tlachinolli. Clearly, it is not a snake. And the “eagle” is not an eagle, but rather a falcon, known in Mexico as a Caracara Quebrantahuesos (Caracara cheriway).

Above is the compound glyph of the atl-tlachinolli. The part of the glyph on the left of the design is made of water and snail shells. The part of the glyph on the right is a strip representing fire.

The compound glyph atl-tlachinolli is placed near the beak of the falcon, not to depict him catching it, but instead is intended to depict the bird singing the word. Other examples of sacred animals shown singing this word can be found on the Aztec war drum, shown below:

A close-up of the animal singing the word atl-tlachinolli, below:

Below is a view of the lower portion of the drum with the depiction of a falcon singing the word:

Below is another drum, this time showing a vulture and a falcon singing atl-tlachinolli:

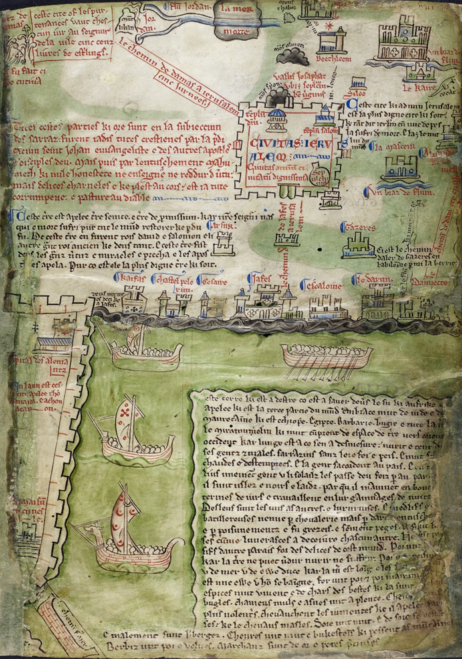

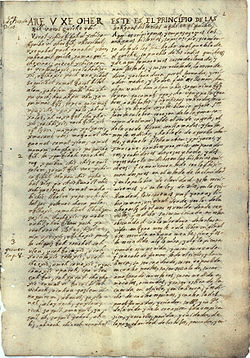

On the page where the myth is explained the codex Mendoza (a.k.a. Mendocino and dated 1540,) shows an eagle perched on a cactus with nothing in its beak, below:

In the Códice Ramírez, also known as the Relación del origen de los indios que habitan en la Nueva España según sus historias of 1587, there is a depiction of an eagle eating a bird instead of a snake or an atl-tlachinolli.

Below, the codex Ramírez 2, also shows the eagle holding a bird in its talons:

Below, the 16th-century Mapa de Sigüenza show a songbird perched on a cactus and singing:

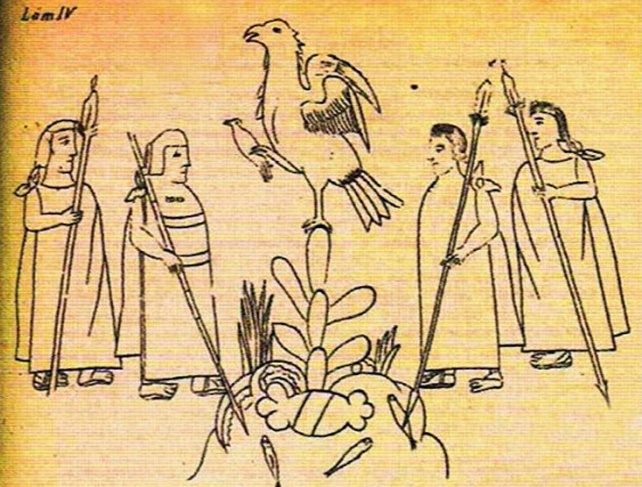

The serpent appeared for the first time in the beak of the falcon (misrepresented as an Eagle) in a drawing in the Atlas de la historia de los indios de la Nueva España e Islas de Tierra Firme by the Dominican priest Diego Duran and dated 1570. In Duran’s drawing, the atl-tlachinolli was substituted with a snake, in an effort by the priest to link the myth with the Catholic idea of good vanquishing evil. Below is a copy of the depiction:

During the Vice Regency period in Mexico, the heraldic eagle was shown both with and without a snake. After independence, the Soberana Junta Provisional Gubernativa decreed on November 2, 1821, that the national coat-of-arms would consist of an eagle with a crown and perched on a cactus.

On April 9, 1823 the Congreso Constituyente provided that “the coat-of-arms is the Mexican Eagle perched on its left foot on a cactus atop a rock that is surrounded by a lagoon and grasping with the right foot a snake and in the act of eating it, and all this surrounded by two branches, one of laurel and the other oak”.

From that point on, the origin of the image (a falcon singing the word “war”) was largely forgotten and the image that was substituted by a Catholic priest in 1570 is the one that now Mexican schoolchildren are taught represents the Aztec legend of the founding of Mexico.