Who was buried in Dzilam, Jean Lafitte, or Pierre Lafitte?

Copyright 2019, Ric Hajovsky

An article in the Louisiana Courier, dated February 22, 1821, says Pierre Laffite left Charleston, South Carolina with a large crew aboard the heavily armed schooner Nancy Eleanor. A woman named Lucy (aka Lucie, Lucia, or Lucille) Allen left with him, as his consort.

On May 7, 1821 Jean Lafitte departed his compound on Galveston Island on his ship the Pride, never to return. Both Lafitte brothers began cruising the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean looking for ships to capture. After departing Charleston, Pierre Lafitte began prowling the waters near Cuba in the Nancy Eleanor, looking for prey. He soon captured a ship that was on its way from Cadiz, Spain to Veracruz. Aboard the captured prize, Pierre and his crew found 1,200 barrels of booze, 900 pottery jars full of olive oil, lace, leather goods, and silver, all worth an estimated total of over $50,000 dollars. They took the captured goods and buried them in Isla Mujeres for temporary safekeeping, leaving some of his men to guard the loot.

Pierre and his crew then took the Nancy Eleanor back out in search of more prey; instead, they themselves were captured. The particulars were kind of muddy, but the National Gazette of Philadelphia reported in April of 1821 that the Nancy Eleanor had been captured by an American cruiser and taken to Old Providence to be sold. There was no word about how Pierre, Lucy and the rest of the crew escaped, but we know that they all showed up back in Isla Mujeres in a smaller vessel armed with only one cannon not long after that.

In October of 1821, Pierre struck a deal with Yucatecan Clemente Cámera; in return for $6,500 cash and a promise give Pierre half the proceeds from taking the buried loot to Campeche and selling them there, Clemente could keep the other half of the profits. Pierre’s master-at-arms, a 26-year-old Canadian from Quebec named George Schumph, witnessed the agreement between Clemente and Pierre, as he later testified after he was captured. (“Notarias Publicas, Protocolos del Afio 1821, “Sumaria instruida contra el inglés don Jorge Schumph, Archivo de la ciudad de Mérida de Yucatán)

While Clemente sailed to Campeche carrying the first part of the captured goods to be sold, Pierre and his crew kicked back on Isla Mujeres and waited for his return. Their stay on the island didn’t turn out to be such a vacation, though. Late at night on October 30, the crew heard a commotion on the beach and went to investigate. To their surprise, they saw it was Comandante Miguel Molas and a dozen of his soldiers and volunteers from the nearby fortified port of Nueva Malaga, on the north coat of Yucatan. (A few years later, Molas would run afoul of the law himself and flee to Cozumel, but that is another story!) Molas heard about the pirates’ presence on Isla Mujeres and was there to arrest them.

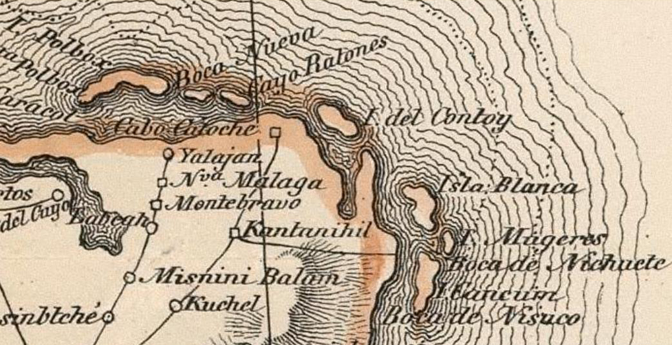

Above: Garcia Cuba’s map showing Cancun, Isla Mugeres, Yalajau, and Nueva Malaga

When Pierre’s men realized they were about to be attacked, they opened fire first. Molas was slightly wounded, as well as a few of his men. Molas’ men returned fire, killing a couple of the pirates, wounding a few, and capturing five, including Pierre and Lucy Allen. Schumph and a few others escaped to their ship and sailed into the darkness. In the morning, Molas loaded his captives into his small vessel and headed back to Nueva Malaga, but he didn’t get far. Schumph and his surviving crewmates were waiting for them with the cannon loaded. Molas had no choice but to turn back to Isla Mujeres, run the boat up on shore and turn his captives loose while he fled the grape-shot fired from the pirates’ 8-pounder. Later, he and his men snuck away in a smaller boat, evading Schumph’s detection and getting away. Schumph, in turn, gathered Pierre, Lucy, and his surviving crewmates and then headed for the protected bay at Bocas Iglesias.

By this time, Pierre was very sick with a fever, as was Lucy. They decided to take Pierre to Dzilam and see if there was a doctor there, but Pierre didn’t make it, dying on the way November 9, 1821. They carried his body to Dzilam and buried Pierre in the church cemetery there on November 10. Soon after that, Schumph and Lucy began walking to Merida, but Lucy died of a fever at Dzemul. Spanish authorities there arrested the young Quebecois under suspicion of being in cahoots with Pierre Lafitte, but Schumph spun a tale of being a Canadian businessman captured by Pierre and all he was trying to do was get away. He was held and interrogated by the Spanish authorities in nearby Merida until December 4, 1821, when they decided to let him go.

The Grave is nowhere to be found

John Lloyd Stephens wrote in his book Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, Vol. 2, that he went to visit Dzilam in 1841, in search of the tomb of Pierre Lafitte a short 20 years after his death, but he did not find it. Stephens’ book describes his search: “The Father was not in the village [Dzilam] at this time, and nobody knows if he [Pierre] was buried in the graveyard or the church, but they supposed as Lafitte was a distinguished man, it was the last. We went there [to the church], and I examined the graves on the floor, and father pulled from a pile of rubble a cross with a name which the father supposed said Lafitte, but it didn’t. The Deacon who was the officer in charge of the burial of Lafitte was already dead; the Deacon went to look for several inhabitants, but a dark cloud covered the memory of pirate; everyone knew of his death, but no one knew where it was or was interested in where he was buried. We also heard that his widow was living in this place, but this was not the truth. It was a black woman who was a servant to the widow, and who, they said, speaks English; the priest sent for her, but she was so intoxicated that she could not come.”

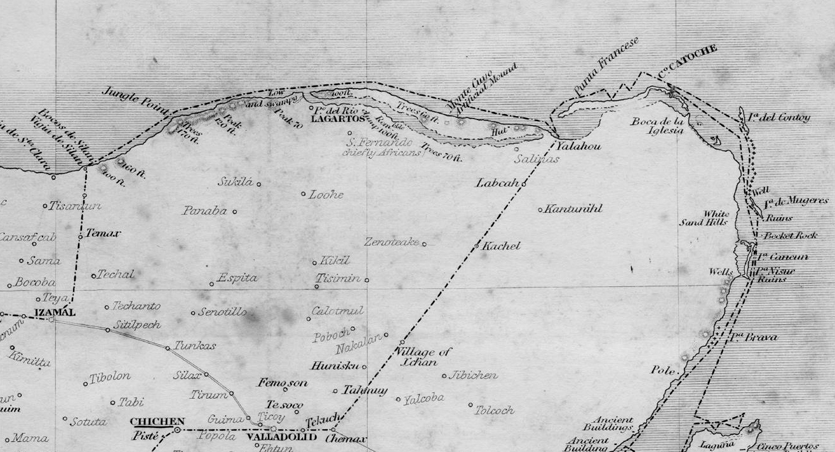

Above: John Lloyd Stevens map showing his route through Yalahou (Nueva Malaga), Isla Mujeres, and Cozumel in 1842. Dzilam is labeled “Silan” on the far left of the map and is where Stevens departed on his voyage to Cozumel and back on the canoa Sol.

The Myth that says Jean was buried in Dzilam instead of Pierre

The often repeated story is that Jean Lafitte died in Dzilam in 1827 or 1828. This story originated in the Mirabeau B. Lamar Papers, a collection of Presidential letters which were published in 1922. What happened was, in 1837, Texas Navy Commodore S. R. Fisher wrote to Texas President Lamar (after Fisher had visited Isla Mujeres on his way to Cozumel to claim Cozumel for Texas, but that is another story!) saying that a turtle fisherman named Gregorio told him that Laffite died of a fever near “Teljas, a small village on the Yucatan coast”. In May of 1838 Fisher again wrote to Lamar, this time saying Laffite died at “Las Bocas, on the north coast of the Yucatan, about 1827 and was buried at Salam [Dzilam]”. It is obvious that Fisher’s source was talking about the death of Pierre Laffite in Dzilam in 1821 and not Jean Laffite. Nevertheless, the story was now in print, so it must be true, and it has been repeated over and over again in books and websites.

The Myth of Pierre or Jean’s Dzilam Descendant

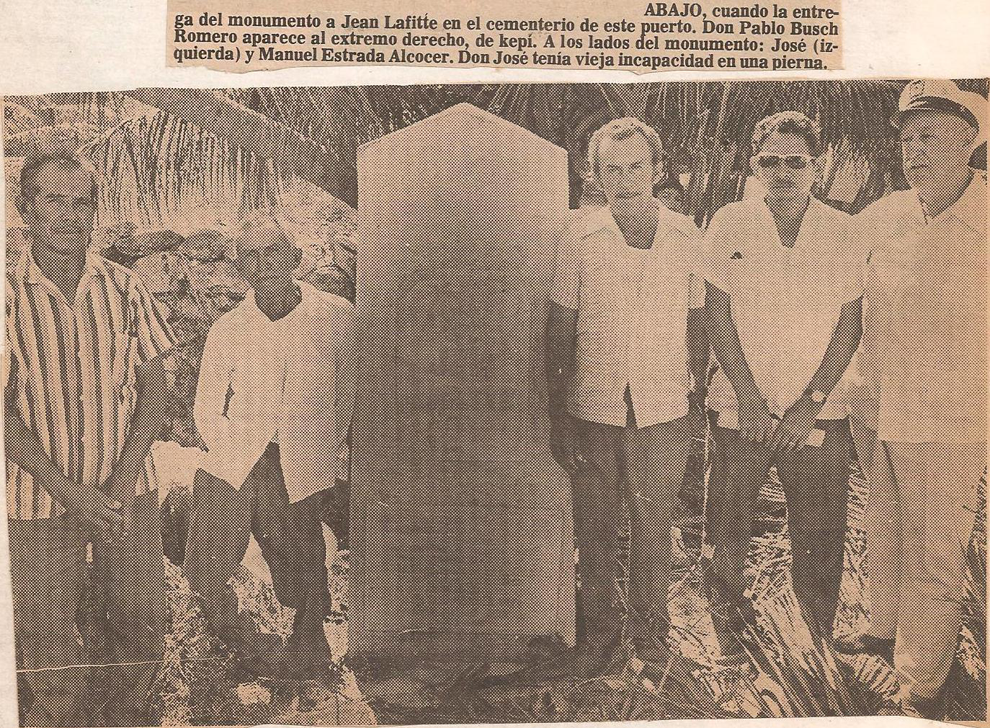

The story that there were descendants of Pierre Lafitte and Lucia Allen in Dzilam began with a tale that Mr. Luis González of Mérida told Pablo Bush Romero in 1958. González told Bush that the consort of Pierre Lafitte, Lucy Allen, gave birth to a girl at Dzilam. Where he got this story is unknown and there is no proof of this legend, but Bush went to Dzilam to investigate it anyway. There, Bush interviewed José M. Estrada Alcocer, a resident of Dzilam. Estrada said that his family was descended from Jean Lafitte, and showed Bush a wooden cross, which was painted with the legend “Jean Lafitte, Re-exhumado, 1938.” Convinced that he just found the burial place of Jean Lafitte, Bush provided funds for a new headstone, in exchange for the old wooden cross.

Above: Pablo Bush (far right) and Jose Estrada (on left of monument with a bent leg) placing the monument to Jean Lafitte in the Dzilam Cemetery. From a July 28, 1960 article in the Novedades de Yucatan.

Above: A close-up of the cock-eyed 1958 inscription on the monument that Bush and CEDAM planted in Dzilam. It is dedicated to Jean Lafitte, not Pierre, and says he died in 1827, instead of 1821. From a July 28, 1960 article in the Novedades de Yucatan.

Not long after, the monument was damaged in a hurricane. Later, another monument to the wrong man was built by the local government using a salvaged piece of the old Bush monument, still bearing the name Jean Lafitte.

Above: Today’s Lafitte monument in Dzilam de Bravo.

The story of the purported genetic connection between Estrada and the pirate Jean Laffite has changed over the years, each time Mr. Estrada told it. For example, in the version Estrada told Lillian Paz Avila when he was 82, he says that he found a human bone on the beach when he was only 8 years old. He told Lillian that the bone was on the beach close to where the old cemetery had been eroded away by the sea. When he showed his find to his mother, she took it to the Dzilam Mayor, who said it was the bone of Jean Lafitte. They then buried the bone in the new cemetery with a wooden cross that said “Jean Lafitte.” Years later, this new cemetery also began to erode, so a third cemetery was built and some of the previous burials were relocated to this new place, including the supposed “bone of Jean Lafitte,” which was marked in 1938 with a cross bearing the words “Jean Lafitte, Re-exhumado, 1938.”

In conclusion:

1. Jean Lafitte did not die at Dzilam and in fact, was never there.

2. Jean’s brother Pierre Lafitte died on the way to Dzilam and he was buried in Dzilam in an old cemetery, which later eroded into the sea.

3. The old 1938 cross marked “Jean Lafitte, Re-exhumado, 1938” was made to mark the burial site of a bone that was found washed up on the beach where the old cemetery eroded into the sea. There is no way to know whose bone that was, but chances are very slim it was from Pierre Lafitte.

4. The consort of Pierre Lafitte, known as Lucia, Lucy, or Lucille Allan, left Dizlam walking to Mérida with George Schumph a few days after the death of Pierre, but she never got there; she became sick and died in Dzemul.

5. The myth that the widow of Pierre Lafitte, (or, supposedly, Jean Lafitte) gave birth to a girl at Dzilam is another legend, nothing more. There are no descendants of either of the Lafitte brothers in Dzilam.