The Birth of the Cruise Ship Industry

Copyright 2019, Ric Hajovsky

When did the Cruise Ship Industry begin? If you guessed the 1920s, guess again. 1820s? Not even close. The Cruise Ship business was well established and functioning in the mid-1300s. That date is not a typographical error; there were cruise ships plying the Mediterranean in the 14th century! They were well organized, money-making machines that took the pious European pilgrims to the Holy Land.

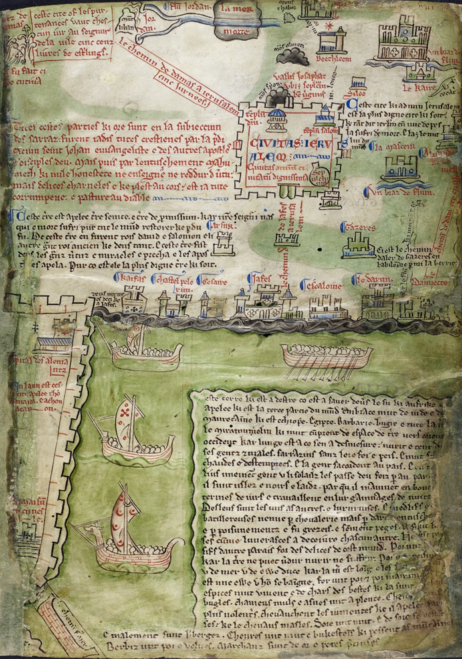

Above: A cruise ship departs from Venice on its way for a cruise to the Holy Land in the 1300s.

The urge to visit the sacred cities and villages of the Bible was just as strong then as it is today; perhaps even stronger. Intrepid travelers would gather their funds, convert them to gold or bills of exchange, and begin to make their way to Venice, where the galleys (ships with both oars and sails) were waiting for the start of tourist season (between April and June) to begin their voyages to what is now Israel.

The pilgrims and tourists who made it safely to Venice were accosted by touts who would surround them, shouting and waving arms to get their attention, each one extolling the virtues of the inn he was representing. They worked on commission, of course. Eventually, the weary travelers would find their way to their respective quarters, where they soon would be cornered by the next round of salespeople. These were the ships’ representatives, each telling their prospective clients about how luxurious his galley was and how dangerous all the others were. These men all offered a standardized contract that had been approved by the Venice government. It provided, for a negotiated fee, the travelers’ sea transport to the Holy Land and back to Venice, two meals a day “fit for human consumption,” the cost of their inns in the Holy land, ground transport (i.e. donkeys) to the sites to be visited, admission fees to the sites (collected by the “Saracens,” or Muslims, who now ruled the area), and the cost of the tour guides (however, the contract specifically excluded the guides’ tips).

First class accommodation aboard was, of course, more expensive. The equivalent of “Tourist Class” was no more than an 18-inch-wide by 5-foot-long space outlined in chalk on the floor deck below the rowing deck of the galley. That deck had no portholes. There, one could spread out one’s mattress or bedroll and try to ignore the din of snores, coughs, and other bodily sounds emanating from your fellow passengers for the next few weeks. Light and air came in only through the hatchways. Persons booking this class of service were prohibited from going on the top deck while the galley was at sea. Bribes were, of course, accepted to allow one to get around this prohibition.

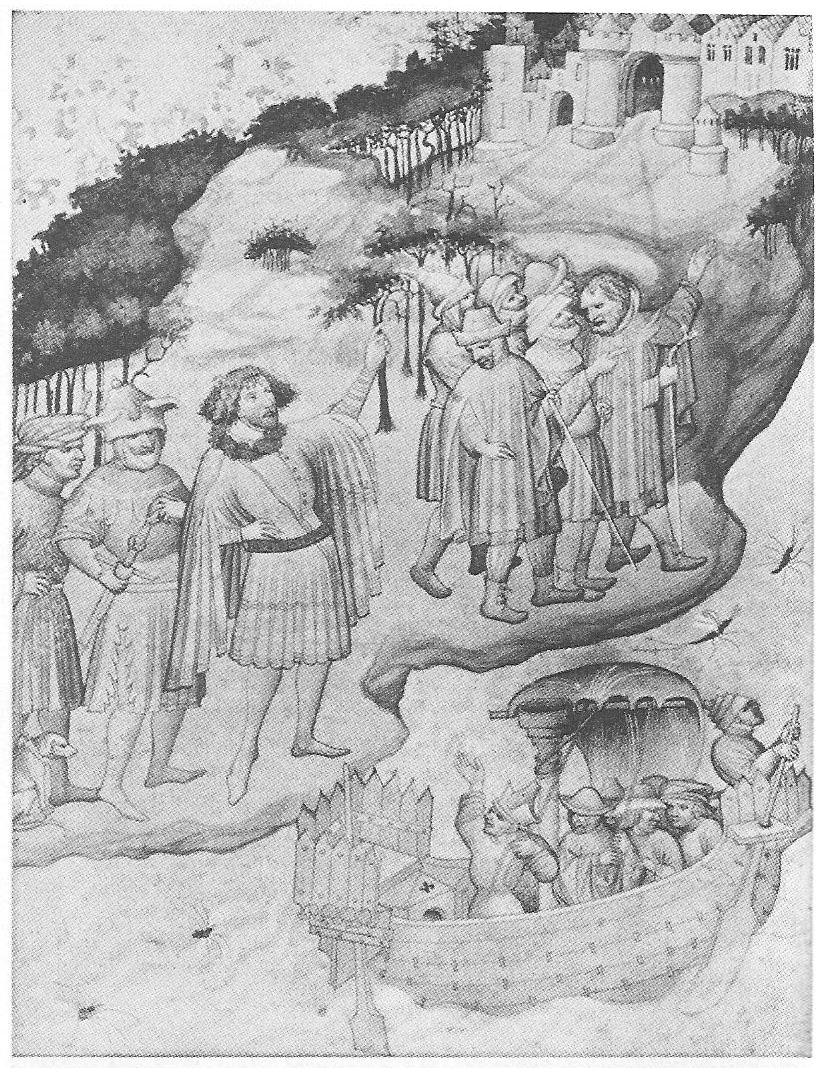

Above: “Tourist class” accommodations below decks was a fetid mess of bodies.

The heat and stench below decks was nearly intolerable, and the space was full of rats, lice, fleas, and other disease-carrying vectors. Not a few pilgrims died along the way. The contract stipulated that anyone dying at sea was to be dumped overboard and their possessions guarded by the captain until the galley returned to Venice, where they would be made available to the next-of-kin. The contract also stipulated that each galley must have a company of no less than 20 cross-bowmen aboard to fend off pirates.

Above: The standardized cruise ship contract stipulated that each cruise ship travel with a contingent of crossbowmen to fend off pirates.

There were several “Rough Guides to Traveling to the Holy Land” available for purchase. One, Iteneraries to Jerusalem, printed by William Wey in 1458, suggested that one go to the shop near St. Mark’s and buy “a fedyr bedde, a matres, too pylwys, too peyre schetis, and a qwylt” and sell them again for half price when you return to Venice. Wey noted that although meals were included, “ye schal oft tyme have need to yowre vytels” and so it was wise to bring along your own snacks.

Above: A 15th century cruise ship “shopping map” showing the pilgrims where to get the best deals.

When all the berths on the galleys were finally sold out, the ships would make their way slowly towards Jaffa, their port-of-call in the Holy Land. Seigneur D’Anglure, in his guidebook Le Saint Voyage de Jherusalem, printed in 1395, remarks that the city was fine and large, but uninhabited. The Saracens knew how to run a port-of-call. No galleys were allowed to let their passengers disembark just anywhere they pleased; the pilgrims were confined to the old abandoned port city of Jaffa, now repurposed into a canton where the Europeans could be controlled and herded much easier than in an actual working port city. From the moment the tourists disembarked, their board, lodgings, excursions, tours, guides, and whole timetable was strictly arranged. There were hundreds of sites to see and they only had three weeks to see them all. The Jerusalem Journey, as it was called in the 14th and 15th centuries, was basically accomplished at a dead run.

As the passengers disembarked, all the ship’s crew, including the indentured rowers, lined up along the quay with their drinking mugs held out to receive a tip. They often reminded disembarking passengers that they were the same crew who would be manning the galley on the return voyage, not without a hint of things to come if a decent tip didn’t fall into their mug. It was expedient, the guide books said, to drop something into every cup.

Above: Cruise ship” passengers beginning their “shore excursion” in the Holy land from Sir John Maudevile’s 15th century book.

Once on shore, the tourists were forced to form a line and give their names to the clerks of the Emir, who wrote each one down and gave the corresponding passenger a ticket, which they were admonished to keep safe at all costs. This ticket would be periodically required by local authorities to verify the bearer’s name against the master list. After the names were taken and the tickets handed out, the vendors were allowed access to the tourists and all hell broke loose. Shouts and cries urging them to buy this trinket or that snack rang throughout the once empty city. For a while, the bedlam seemed insurmountable, but eventually the last penny was squeezed out of the bewildered visitors for the day and the vendors were made to retreat. The passengers were herded together once more, now burdened with souvenirs and “saints’ relics” and ushered into their quarters for the night. It had previously been a stable, but now served quite well as a “tourist quality inn.”

Above: Souvenir sellers were just as pushy back then as the ones on Avenida Melgar today!

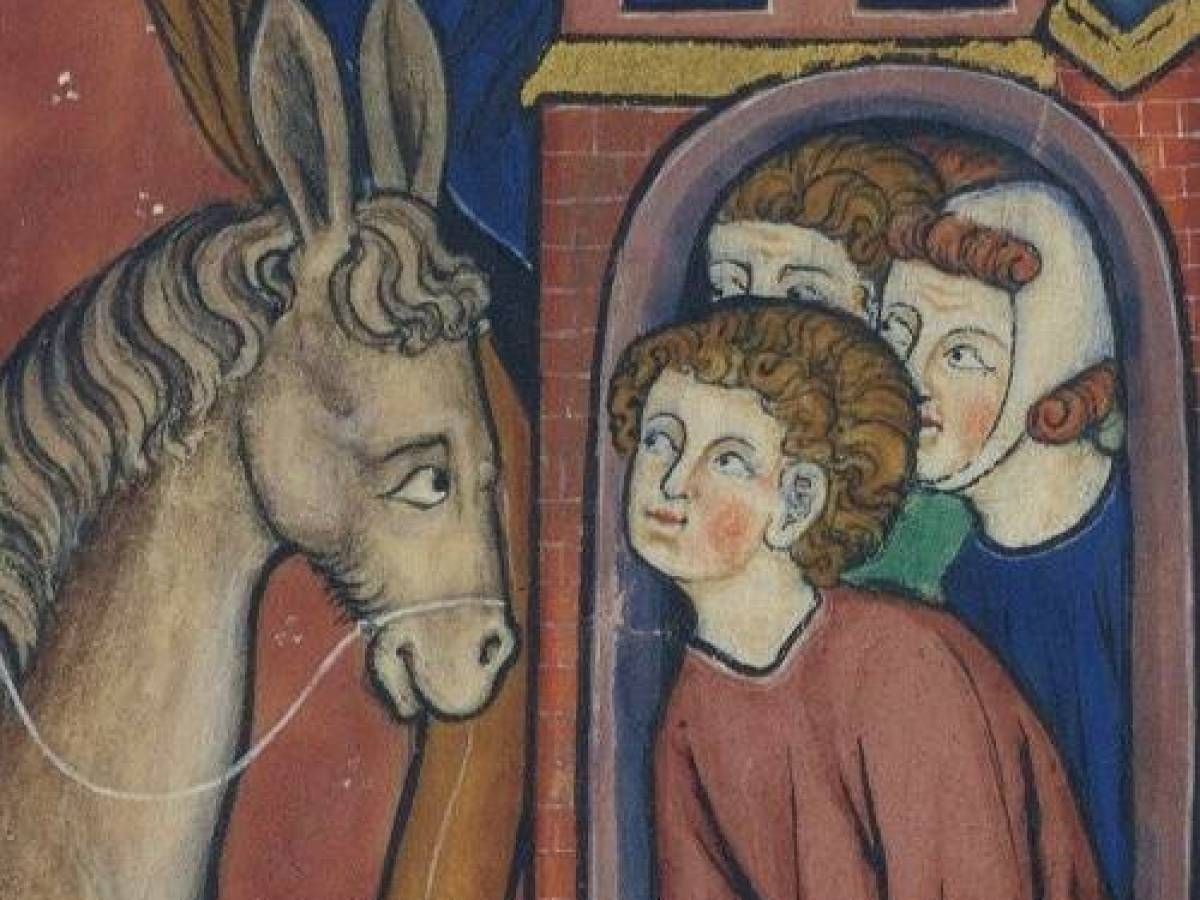

John Poloner’s Description of the Holy Land, written for the traveler of 1421, warned that no one should attempt to break the rule prohibiting anyone from leaving the inn unaccompanied. The Saracens, he stated, were fond of catching the wayward traveler on one of these illicit strolls and demanding a payment from him to avoid being thrown in jail for the offense. In the morning, the guide books warned that it was advisable to get up early “for and ye come by tyme ye may chese the beste mule… for ye schal pay no more fore the best then fore the worst.”

Above: Choose your mule early.

Once mounted and all the baggage loaded, the entire shipload of passengers headed in single file towards the next destination; Ramleh. Here, the ships’ captains, who acted as the “G. O.” or gentile organiser, of the trip, lined the passengers up and laid down the rules for the rest of the shore excursion of the trip:

1. One should never go out without an official guide.

2. Hands off the Saracens’ womenfolk.

3. Do not drink alcohol in the presence of a Saracen; but if you must, ask that “yore comrade stand afore hem and cover hem withe his cloke.”

4. Refrain from scratching or painting names or coats-of-arms on monuments, as well as from chipping off pieces of holy places or making any marks on them.

5. Finally, do not forget to tip your guide each day.

Marjorie Kemp, an English woman who made the trip from Venice to the Holy Land in 1413, described the whirlwind tour in her biography, later translated from her medieval English into our modern version and renamed Memoirs of a Medieval Woman. Marjorie’s account is a blur of countless stops, all designed by the Saracens to extract the maximum amount of money from each traveler. To touch the actual crib that baby Jesus slept in cost an extra two pennies. A hair from the mummified head of John the Baptist was an extra three. To stay inside the Church of the Holy Sepulcher overnight, priceless.