Shadow on the Stairs: A story of mass delusion

Copyright 2015, Ric Hajovsky

Today, the great pyramid at Chichén Itzá (known as El Castillo), is covered with a smooth and unbroken sheath of limestone blocks. The stairways are also made up of finely-cut limestone and the balustrades are straight, square-edged, and well defined. It is due to this sharp-edged veneer of stones and the arrow-straightness of the balustrade that the corner of the pyramid is able to cast its seven triangles of light and shadows on the side of the staircase during the spring and fall equinoxes.

There is no question that the shadow appears. The question is who is responsible for the calculations that went into placing the huge pyramid so precisely that this shadow effect happens only at that time of the year? The tour guides, websites, and popular books all agree that it was the ingenuity of the ancient Maya that accounts for this amazing feat of engineering. However, the answer actually is that the shadow is an accidental result of the reconstruction (note I did not say “restoration”) that the pyramid underwent in the 1920s.

What happened was, the Mexican government made a coldly-calculated decision. Based on the advice of Alfred Kidder of the Carnegie Institute, a plan was designed in which two goals could be met: The American institute could have permission to excavate selected sites in Chichen Itzá, and the Mexican Government could reconstruct certain buildings in the ruin site with the funds provided by Carnegie. The idea of the Mexican government was to build a first class tourist attraction. One government document written in 1921 stated: “Si se puede mantener Chichén Itzá como lugar interesante y bello, va a volverse, sin duda, una Meca turística y un recurso valioso…”

Miguel Angel Fernández was in charge of the initial stage of the restoration work undertaken at the Castillo and the Ball Court in Chichén Itzá. He was a slow and methodical worker, using only original stones from the ruins to restore and stabilize them. He worked on the project from 1922 until 1924, but left when he was presented planes with which to REBUILD certain of the ruins according to the government’s idea of what the ruins should look like, not based on any archaeological evidence, but rather towards the goal of making an eye-popping tourist attraction. Before he left, however, he oversaw the start of the rebuilding of the stairway (with all-new stones) and the recovering of two faces of the pyramid with newly cut limestone, which replaced the old stone covering which had been carted off years earlier and reused as building material on nearby ranches.

Archaeologist/architect Daniel Schavelzon wrote in his 1986 article, Semblanza: Miguel Angel Fernández y la Arquitectura Prehispánica (1890-1945): “Es evidente que la reconstrucción exagerada y sin demasiadas evidencias que se hizo en el Juego de Pelota —en especial la de los dos templetes—, contrastara notablemente con el minucioso trabajo de anastilosis que Fernández había hecho en el mismo conjunto. Y ni hablar de las contradicciones existentes entre su restauración y su consolidación del Templo del Castillo y lo que hizo más tarde.” “It is evident that the exaggerated reconstruction made with little evidence in the Ball Court – especially that of the two temples – contrasted markedly with the meticulous work of anastilosis* that Fernández had done in the same set. Not to mention the contradictions between his restoration and his consolidation of the Templo del Castillo and what they did later.” * Anastylosis is an archaeological term for a reconstruction technique whereby a ruined building or monument is restored using the original architectural elements to the greatest degree possible.

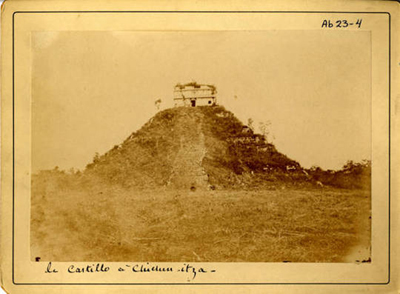

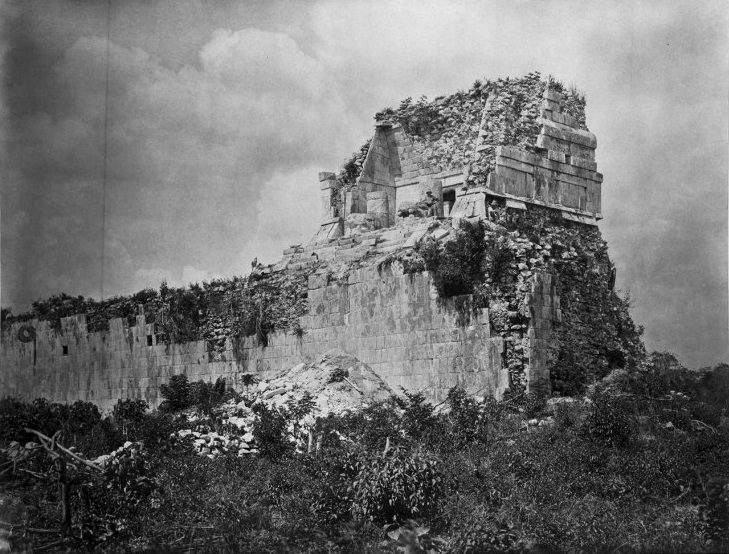

Above: The pyramid as it looked in 1860.

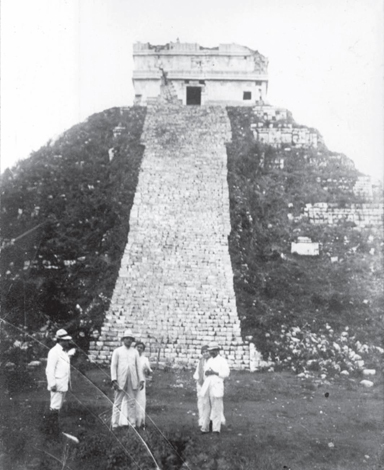

Above: The pyramid in 1905.

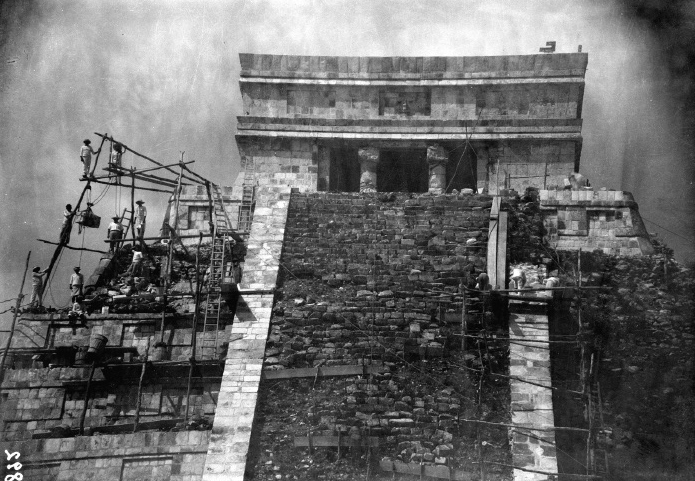

Above: Reconstruction began in 1910 with the building, from scratch, of a new stairway. This first attempt at rebuilding the stairs with recycled stones was later torn out and new blocks cut for the stairs.

In 1922, the serious reconstruction work began. New stones were cut for the veneer, and the taluds and tableros of the pyramid’s sides were rebuilt from the bottom up.

The stairway balustrades, which had been removed and reused as building material long ago, were rebuilt from scratch.

The temple at the top of the pyramid was rebuilt as well.

Little by little, the new pyramid began to take shape:

Above: The pyramid in 1925, nearing completion.

Above: The newly rebuilt pyramid in 1929, in a photo taken by Charles Lindbergh.

The shadow was first noticed in 1928, but since the archaeologists were aware of their drastic rearrangement of El Castillo pyramid’s exterior, they paid no attention to it. It was not until 1973 that Mexico City attorney Luis Enrique Arochi Flores saw a photograph of the shadow and began telling people about it and linking it with the god Kukulcán. He later published a small book about the shadow, La Pirámide de Kukulcán, su simbolismo solar.

Not long after Arochi visited Chichén Itzá to photograph the shadow for himself, tour-guide and self-promoter Adalberto Rivera began to tout the phenomena to tourists. By 1976, the Yucatan government had taken notice of the new interest being generated in El Castillo, and decided to begin promoting the idea in order to boost attendance. Riviera used his connections with INAH in Mexico City to get named the “Official Interpreter” of the phenomenon, alienating some of the state officials. He lost his quasi-governmental position in 1996, but made a comeback in Cancun selling his book on the subject, which blended Gnosticism, spiritualism, numerology, and various symbols from Far Eastern religions into the phenomenon.

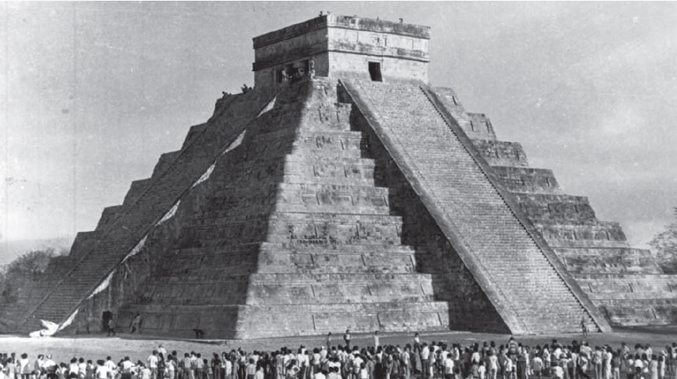

Above: The attendance during the event in 1975 was more than anyone expected.

In 1982, José Díaz Bolio, a writer, poet, and aficionado of archaeology, wrote his book La Serpiente de luz de Chichén Itzá. This book just added fuel to the fire. Attendance at the ruin site during the equinoxes began to spike, and newspaper articles and news broadcasts started promoting the event. Soon the state government in collaboration with INAH began to selling the idea of an equinox ritual for tourists. The idea worked much better than anyone’s wildest dreams and now over 90,000 people visit the ruins each year during the equinox periods to enjoy performances by dancers and musical groups.

In 2007, Chichén Itzá was named one of the “New Wonders of the World” by the private commercial organization “New7Wonders Foundation,” in a contest held via the internet that was open to unlimited, multiple votes by organizations promoting their country’s particular entry. The contest received much criticism at the time and was boycotted by several countries because of its unscientific methods of recording votes.

Above: El Castillo today, shortly before they stopped people from climbing up the stairs. This prohibition was not made to protect the new stones, but to stop people from falling after a tourist fell to her death while climbing on the pyramid.)

El Castillo wasn’t the only ruin in Chichén Itzá to be rebuilt to be what the government thought the original building “should have looked like.” The Temple of the Warriors and the East Temple of the Ball Court were reconstructed as well. The East Temple at the Ball Court was in terrible shape when it was discovered. The front face and roof had fallen away and many of its stones had been stolen, to be reused as building material. Below is what it looked like in 1889:

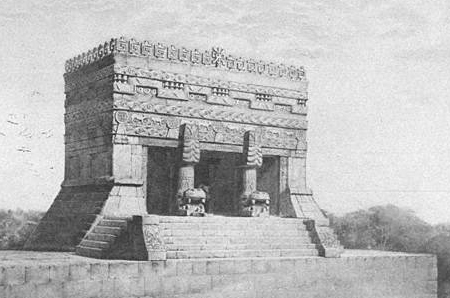

So a plan was drawn up of how they wanted the building to be reconstructed, not based on any evidence of how it may have looked originally, but instead they used a hodge-podge of design elements copied from buildings on other Maya sites…

… and then they rebuilt the temple exactly according to that plan:

As is plainly clear, the new, reconstructed façade of the building is a complete invention, dreamt up by Alfred Percival Maudslay, the one who drew the plans for the rebuilding of the structure.

The same process was applied to the Temple of the Warriors. Below is what it looked like when it was discovered:

Below is what it looked like during its reconstruction:

And, finally, below is what it looked like when the work of building it anew was completed:

To read more about the crazy myths, wacky theories, and well-publicized misinformation about the ruins at Chichén Itzá, check out my book on the subject at Amazon Books