Bases, Bulldozers, and Bullshit

Copyright 2011 Ric Hajovsky

PAN AMERICAN AIRWAYS AND COZUMEL

Pan American Airways was initially a shell corporation founded by US Army Major Henry “Hap” Arnold in 1927 as a front to keep the German airline SCADTA from winning landing rights in Panama. The German line had already an established route that they had been flying since 1920 that went from Colombia, Roatan, Belize City, Cozumel, Havana, to Miami. Arnold was concerned that SCADTA, operating out of Colombia, was angling to get landing rights in Panama in order monitor movements in the canal. Even though his new company had no airplanes at the time, Arnold was able use his influence with the US Government to win a contract to deliver US Mail from Miami to Havana. Later, by joining forces with two other airlines (one company that had one plane, but no landing rights, and another that had landing rights in Havana, but no plane) Arnold was able to fulfill the terms of the contract. He next tendered bids for contracts on all the new US Mail routes (F. A. M. routes) between the US and Central and South America, winning every one of the contracts in 1928, thus denying SCADTA the Panamanian landing rights. In a move to thwart competition and get its hands on more planes, Pan Am then purchased Compañia Mexicana de Aviación (for a mere $150,000USD) and spun it off as a subsidiary the same year, allowing Mexicana to continue to operate in Mexico under the same name.

In January, 1929, Pan Am made its first passenger-carrying flight, from Miami to San Juan via Belize and Nicaragua. In February, 1929, Charles Lindbergh flew the first Pan Am mail flight to Panama, refueling at Cozumel in a twin engine, ten- passenger, Sikorsky S-38 flying boat.

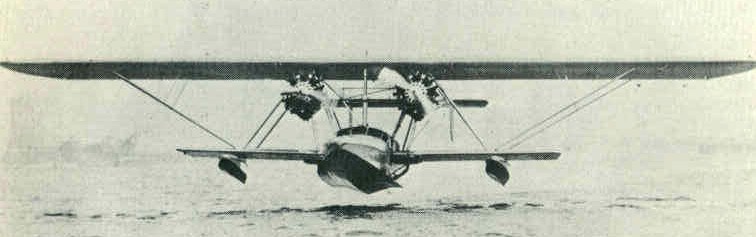

Above: Pan Am Sikorsky S-38 in Miami

In October, 1929, Lindbergh again landed a Sikorsky S-38 flying boat at Laguna Ciega in Cozumel when he flew several Carnegie Institute archaeologists to the island for the night after making an aerial reconnaissance of Mayan ruins on the mainland.

That same year, Pan-Am began a weekly seaplane service between Miami and Panama. That route had several fuel stops along the way, including one in Cozumel. A copy of one of Pan Am’s old 1929 schedules showed the stop on the island was only 30 minutes, from 1:45 PM to 2:15 PM.

Pan Am Sikorsky S-38 coming in for a landing on the water

In February, 1929, Charles Lindbergh flew the first Pan Am mail flight to Panama, refueling at Cozumel in a 10 passenger, twin engine, Sikorsky S-38 flying boat. In October, 1929, Lindbergh again landed a Sikorsky S-38 flying boat at Laguna Ciega in Cozumel when he flew several Carnegie Institute archaeologists to the island for the night after making an aerial reconnaissance of Mayan ruins on the mainland.

That same year, Pan-Am began a weekly seaplane service between Miami and Panama. That route had several fuel stops along the way, including one in Cozumel. A copy of one of Pan Am’s old 1929 schedules showed the stop on the island was only 30 minutes, from 1:45 PM to 2:15 PM.

A Pan Am Sikorsky S-38 at the seaplane ramp at Calle 3 and the malecon in San Miguel in 1929

Later, between 1930 and 1935, seaplanes used a ramp built by Oscar Coldwell on the seafront near Calle 3 sur. Although there had been a small airstrip on Cozumel prior to October, 1929, in April 1930, José R. Juanes, the representative of Pan American’s subsidiary Mexicana, announced the purchase of 160 hectares of land north of San Miguel to build their new Campo de Aterrizaje Cozumel (landing strip), where passengers could connect with a Mexicana flight to Mexico City via Merida. Pan Am discontinued the Cozumel stop in July, 1931 and rerouted its flights through Merida. On April 15, 1932, the Islanders took up a collection to repair the airstrip (total amount donated: $25) and Pan Am re-instituted the service. In 1933, Compania Aeronautica Jesus Sarabia S. A. (Sarabia) began to use the island’s airstrip for twice-weekly connections to Merida and Chetumal until the airline suspended operations in 1942 and was sold to TAMSA in 1943.

COZUMEL DURING WORLD WAR II

Even before the US was drawn into the war by the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, the American military was worried about how to defend the Panama Canal from possible attacks by Japanese carrier-based planes. The US had to be able to fly its warplanes south to Panama as needed and Washington began negotiating with the Mexican government for the rights fly US military planes through Mexican airspace, refueling them at air bases in Tehuantepec and the Yucatan. Of the several landing fields available in the Yucatan, the campo de aterrizaje in San Miguel de Cozumel seemed to be the best option. Permission to improve the strip was requested by the US and granted by Mexico in August, 1941, as well as the rights to use the Pan American Airways’ field at Merida until the work on the Cozumel field was completed, which was expected to take about a year. The US government planned on contracting Pan American Airways to perform the work on the Cozumel airstrip. Pan American, in turn, would sub-contract the work to its Mexican subsidiary Compañia Mexicana de Aviación. Consequently, and all work was to be done at the proposed San Miguel airbase by a Mexican company utilizing Mexican labor, as required by the agreement with Mexico. The agreement also specified that once the field had been up-graded (with funds to be provided by the US) the field would remain under the control of the Mexican military.

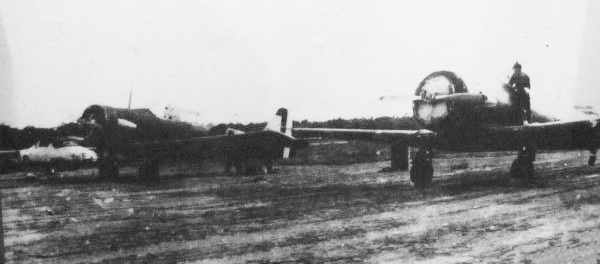

Cozumel’s dirt airstrip in late 40s early 50s

Upon hearing that a contract to begin work on the airport was going to be let, Cozumel’s Agrupación Obrera Mixta de Trabajadores Marítimos y Terrestres (Union of Maritime and Inland Workers) sent Ramon Zapata and Juilio C. Mac to Mexico City in 1941 to lobby for construction jobs for union workers on the project. The lobby effort failed and in 1942 Compañia Mexicana de Aviación sub-contracted the work to Mexicana Constructora Azteca, S. A., a Mexican company that had also worked earlier on Mexicana’s Mérida airport. Constructora Azteca then began flying in workers from outside of Cozumel to do the work.

In May, 1942, German submarines sank two Mexican merchant vessels in the Gulf of Mexico. Mexico did not immediately declare war against the Axis, but instead demanded an explanation from the German Embassy. A few days later, they got the Germans’ response; a U-Boat sank two more Mexican merchant vessels. The Fuerzas Areas Militares (FAM) was at the time a poorly equipped branch of the Mexican military and did not have the airplanes with which to mount anti-submarine patrols, so they requested help from the US under the “Lend/Lease” program that the US congress had enacted, for cases just like this. The US responded by

immediately delivering a group of Vought Kingfisher OS2Us to FAM (the Mexican air force) so they could begin patrols and followed up shortly thereafter with the delivery of a group of North American AT-6s, Beech AT-11s, and Douglas A24s. In addition to the planes, the US also gave Mexico funds to operate the planes together with the supplies and parts to maintain them. In June, 1942, FAM General Roberto Fierro Villalobos, Chief of Mexican Military Air Operations, designated Colonel Alfonso Cruz Rivera as Commander of the 2nd Air Regiment and put him in charge of the Gulf Region, which included the Gulf of Mexico, the Caribbean, and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Colonel Cruz then sent the 3rd, 4th, and 5th squadrons of the 2nd Air Regiment to begin flying the Voughts and some old, outdated, Consolidated 21-M bi-planes (planes that FAM had on hand from before the war) on anti-submarine patrols from the air strips in Tampico, Veracruz, Merida, Ixtepec, and Cozumel. In July, 1942, the US requested that in return for the planes it had given to Mexico, US forces be allowed to use the air strip at Cozumel as a base to carry out their own anti-submarine operations in the Caribbean. The request was granted, or so the US thought.

Above: Dirt strip on Cozumel in 1942

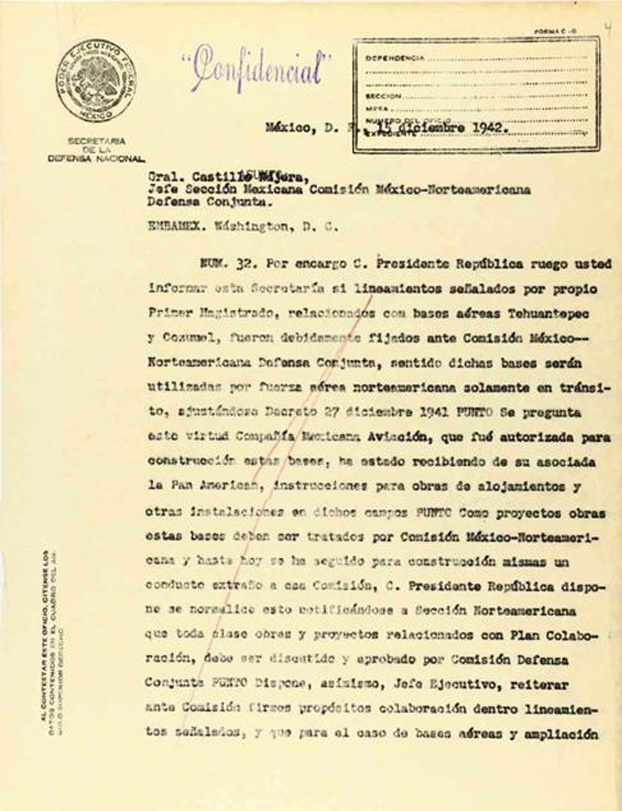

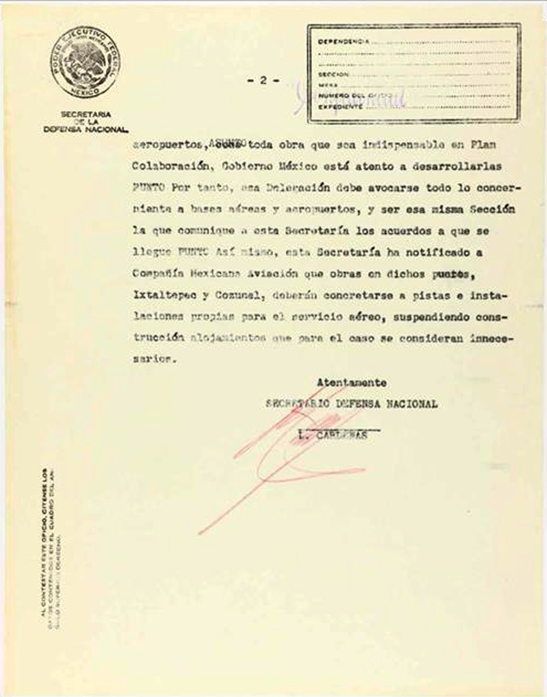

However, in November 1942, W. L Morrison, the manager and director of Compañia Mexicana de Aviación’s construction projects at Tehuantepec and Cozumel, was summoned to the office of Mexico’s Secretary of Defense, ex-President Lázaro Cárdenas, the very man who had nationalized Mexico’s oil reserves and ended US and other foreign oil company operations in Mexico in 1938. Morrison was also told to bring the plans for the improvements scheduled to be installed at the two fields. When Cárdenas was shown the plans, which included a number of buildings Mexicana was going to build in addition to improving the runways, he wanted to know why all the structures were needed, since Mexico had never agreed to allow American servicemen actually stay in either Cozumel or Tehuantepec. Cárdenas had a letter sent to Washington DC (shown below) saying that said the agreement was only that the US could use the air strips in transit and could not build barracks or station troops at either at Cozumel or other Mexican airstrips.

After the meeting with Cardenas, Morrison reported back to Pan American that Mexico was worried that these planned buildings indicated the US intended to station US servicemen at the two bases, and that the Mexican government was opposed to that. The Mexican government’s position was that no foreign troops, even if they were Allied troops, would be allowed to man bases on Mexican soil. US technicians could be allowed to operate and service radar emplacements along the West Coast of Mexico as they taught Mexicans how to do the job, but only if they came in very small numbers. They would not be allowed to be stationed in Cozumel. This unsettling news was passed on the US War Department, and they were still trying to understand what was going on when, two weeks later, Mexican Secretary of Defense Cárdenas told Compañia Mexicana de Aviación they were forbidden to build any lodgings, commissaries, or other buildings in either Tehuantepec or Cozumel, and that they were only allowed to improve the existing runways there, nothing more. Cardenas then informed his US counterpart that he had halted construction of the two bases, claiming it was only a temporary interruption while they studied the matter. However, the authorization to continue construction never came. In order to protect the Yucatan Channel from German submarines, the US began flying anti-submarine missions out of San Julian, Cuba and the Cayman Islands, countries which welcomed the presence and protection of US military.

Above: Mexican President’s representative inspecting the campo de aterrizaje in San Miguel de Cozumel

Below is a copy of the letter Mexico sent to the US denying them the use of Cozumel as an US airbase or even letting US servicemen staying on the island overnight.

By December, 1942, the tide of the war was turning in favor of the Allies. The Japanese threat to Panama was gone and the German U-boats had been recalled by Berlin from the Western Atlantic so they could help protect North Africa. Consequently, the Mexican airbases were no longer important as before, and the work stoppage at the Cozumel airfield was not contested by the US. In a memo to the chief of staff dated February 11, 1943, the situation concerning the Mexican Secretary of Defense’s opposition to the planned airbase on Cozumel was summarized thusly:

“The general strategic situation in the pacific underwent a decided change as a result of our successes in the South Seas. This and other considerations made it appear more and more questionable whether the War Department should proceed further along these lines [of building airbases in Mexico]. Among the considerations was the naming of Cárdenas as Minister of National Defense of Mexico and the full realization by representatives of the War Department that at no time except in dire emergency would units of US air or ground forces be permitted to use such defense facilities as might be constructed in Mexican territory.”

On September 1, 1943, the following memo appeared in the US World War II War Diaries, showing that the two dirt runways on Cozumel were still not finished being improved at that time:

By 1944, one part of the Cozumel airstrip was being maintained by Pan Am only for use in emergency landings. The other part was occupied by the Mexican Military. After the end of the war, Transportes Aeros Mexicanos (TAMSA) began flying from Cozumel to Isla Mujeres, Carrillo Puerto, Chetumal, Merida and Belize six days a week, beginning in October, 1945.

BASES, BULLDOZERS, AND BULLSHIT

In Cozumel, there is an oft-quoted story that tells of a Mayan city north of the downtown area of San Miguel that was bulldozed into oblivion by the Americans when they built a military base on the island. Sometimes the villain is the US Navy, sometimes it is the US Army, sometimes it is the US Air Force, and sometimes it is the US Marines. Occasionally, it is the Seabees or the US Corps of Engineers. Regardless of the branch of service these evil-doers belonged, they were always described as American. Sometimes they were supposed to have built a submarine base. Sometimes it was an airbase to launch anti-submarine sorties over the Caribbean. Sometimes it was a base to train WWII Frogmen. Multiple variations and permutations of this story have been printed and reprinted in guide books, web-pages, and magazine articles so many times that they are too numerous to count. A few of the most typical versions are:

The largest Maya ruins on the island were bulldozed to make way for an airplane runway during World War II. Cozumel Sights

During World War II, the United States built an airstrip on Cozumel and operated a submarine base. Diving Cozumel

During World War II, the US army built an airstrip and maintained a submarine base on the island. Unfortunately they also dismantled some of the larger Maya ruins, not realizing what they were destroying. Fodors

During World War II, the Americans built an airstrip and a submarine base on the island, where Marine Corps divers trained for upcoming events in Europe and the Pacific. The Caribbean Dive Guide

The American Army Corps of Engineers built an airstrip on Cozumel where the Allies also maintained a submarine base. Guide to the Yucatan Peninsula

A US submarine base was maintained there during World War II. Encyclopedia Americana

Obviously, the writers of these misleading stories made no effort to actually research the facts, they just copied and recycled the mistakes and misunderstandings printed in previous guide books. While the truth is that the US may have wanted to fly anti-submarine missions out of Cozumel, the Mexican government never allowed them to use the island as a base for submarine chase/spotter planes, let alone allow them to build any submarine pens with which to dock and service allied submarines. As a matter of fact, the US never even operated any of its submarines in the Gulf or Caribbean during WWII, since there were never any German or Japanese surface ships operating in that area.

So, just who was it that began to improve the old Campo de Aterrizaje Cozumel in 1942? Grupo Aeroportuario del Sureste S.A. de C.V. (Asur) is a holding company that, through its subsidiaries, is engaged in the operation, maintenance, and development of nine airports in southeastern Mexico. ASUR, states that “during the 1940s, the federal government [the Mexican Federal Government] built a number of others [runways] with World War II aid from the United States. Those in Asur’s future territory were in Campeche, Chetumal, Ciudad del Carmen, Cozumel, Itxtepec, Merida, and Veracruz.” The Cozumel runway not paved until the Mexican government lengthened and paved them in the early 1960s. Up until then, the runways (built by Mexicana in 1929 and slightly improved in 1942 Constructora Azteca, S. A.) had been dirt.

Sign marking the entrance to FAM Base Area No. 4 (COZUMEL) in 1950

But, what about the story of the bulldozing of the Mayan ruins to make an airstrip? While it is possible that some vestige of the outskirts of Xamencab (the Mayan village that Grijalva, Cortes, and others reported visiting in the early 1500s) was destroyed in 1942, when the Campo de Aterrizaje Cozumel was improved, it is obvious the Americans could not have been the ones responsible, since the Mexican government was so adamantly firm in their position that all work to be done under the agreement covering the airstrips in Tehuantepec and Cozumel be carried out by Mexican laborers and employed by a Mexican company, in this case Compañia Mexicana de Aviación and Mexicana Constructora Azteca, S. A. But, even if even if either one of these Mexican companies had destroyed of a few ruins north of the city of San Miguel in 1942, that loss would seem insignificant when compared to what the Cozumeleños themselves did to the remains of the Mayan buildings and temples that comprised of the bulk of Xamencab.

There is plenty of eyewitness accounts detailing the plethora of Mayan and Spanish Colonial ruins that were once standing within the boundaries of what is today’s downtown San Miguel. In 1831, James Bell wrote about the island, stating “The ruins of European edifices on the island of Cozumel, in the midst of a grove of palm trees, indicate that the island, now uninhabited, was, at the commencement of the conquest, peopled by Spanish colonists.”

Below is a drawing made after one drawn by Frederic Catherwood of a temple that was located in the town when he and John Lloyd Stevens visited the island in 1841. Why is there no sign left of this temple today?

The ruins of the old Spanish church were also described by Stevens in the book Incidents of Travel in the Yucatan. In the chapter on Cozumel, Stevens says they saw “…the ruins of a Spanish church, sixty or seventy feet front and two hundred deep. The front wall has almost wholly fallen, but the side walls are standing to the height of about twenty feet. The plastering remains, and along the base is a line of painted ornaments. The interior is encumbered with the ruins of the fallen roof, overgrown with bushes; a tree is growing out of the great altar, and the whole is a scene of irrecoverable destruction.” Again, what happened to these ruins?

Fifty-four years later, in 1895, William Henry Holmes also visited the island. He later wrote: “there were large masses of shapeless ruins and mounds around the area of the old church.” Holmes went on to say: “The intact ruins mentioned by Stevens, were not to be found. In front of the ruins of the ancient Spanish church of which he speaks at length there is only a shapeless mound to represent the temple at that point.” After walking about a mile north of the village of San Miguel, Holmes described a shrine he found at a location called Miramar, which had a doorway supported by a column bearing a bas-relieve carving of a female giving birth. He sketched and photographed the nearly intact temple, which is a good thing for us, since it has since been dismantled and the main column carried away. It now is housed inside the Museo de la Isla. Holmes went on to describe another temple nearby and then observed it was “in an advanced state of ruin. The ready-cut stone of these buildings is so much more easily utilized for fences and building purposes by the present residents than is the rock in place — though the limestones are all soft and easily quarried along the natural exposures everywhere occurring — that it is surprising to find even these remnants left.”

In 1940, prior to any significant improvements to the original 1929 Pan Am air strip on Cozumel, Henry Raup Wagner visited the island while researching his book The Discovery of New Spain in 1518. Wagner postulated that the Mayan village of Xamencab and its temples reported by the early Spanish explorers were located exactly where the town San Miguel lay. He further theorized that was why no ruins have been found in that location; that since the construction of the streets and buildings of this rather large town would have consumed far more than the limestone blocks than easily quarried, the Cozumeleños simply re-utilized stones from the ruins of the houses, halls, and temples reported by Grijalva, Cortes, and the others.

I have witnessed this re-purposing of the Mayan temple’s stones and columns myself. In the early 1980s, I leased an old Cozumeleño home at the corner of Avenida 5 and Calle 8. I intended to use the building to house an offset printing shop, but when it came time to bring in the presses, the doorways proved too narrow. I had to ask the owner for permission to widen one of the building’s doorways in order to get the presses inside. When the albaniles began swinging their sledges and tearing into the two-foot thick wall, it turned out the stones used to build the house had been scavenged from Mayan structures. Round columns, dressed square stones, lintels, and metates were stacked up one on top of another like so many concrete blocks. Multiply the size of that opening we made by the volume of the rest of the house’s standing walls, and you’re talking about enough scavenged archaeological material to construct all the buildings in the main plaza of San Gervasio. Multiply the amount of re-used Mayan building material in that whole house by the number of other houses of the same age and construction in the immediate area, and you’re talking about enough dressed stones to build an entire Mayan village.