The Maya did not Invent their Calendar, Writing, or Numbering System.

Copyright 2019, Ric Hajovsky

Today, it is de rigueur, to credit the Maya with all sorts of incredible achievements. However, “incredible” (as in “unbelievable”) is the key word here; most of the “firsts” attributed to the ancient Maya in Wikipedia and other popular websites are not true. For example: What we now call the “Mayan calendar,” was not invented by the Maya. It was invented by an earlier civilization that we now call the Zapotecs, some 2,500 years ago (around 500 BC).

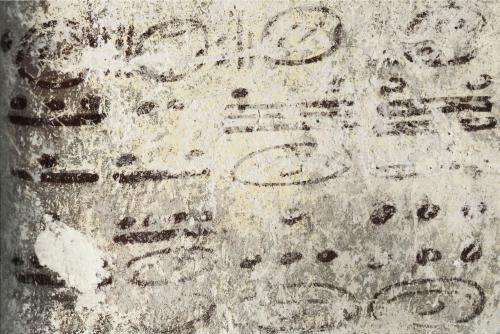

Above: Zapotecs carved their long-count calendar 2,500 years ago on Stelas 12 and 13 at Monte Alban in Oaxaca.

The oldest known version of the Mayan calendar, on the other hand, is dated just 1,200 years ago (800 AD). That is 1,300 years after the Zapotecs already came up with it. The Zapotec and Mayan calendars were virtually the same; the 20 day-names and 13 numbers were both arrived at through the same “wheel-within-wheel” mechanism utilizing a 260-day sacred calendar and a 365-day solar calendar.

Above: The earliest example of the Mayan calendar was found at Xultún, Guatemala. It is only about 1,200 years old.

The Epi-Olmec were among the first New World civilizations to invent the concept of zero, another invention that is often mistakenly attributed to the Maya. Many other cultural aspects of the Epi-Olmec civilization predated the Maya use of them, such as sacrificial bloodletting, rubber production, and the use of a ceremonial ball court, and the “dot and bar” numbering system, to name a few. Several of the gods that were later revered in the Maya culture first appeared as Epi-Olmec gods, such as a feathered serpent, the corn god, and the god of rain.

Mayan Writing System

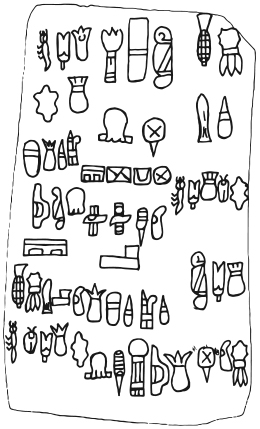

The Maya did not come up with their system of writing independently as commonly believed; their system was adaptation of earlier Mesoamerican writing systems, like those developed by the Olmecs, Epi-Olmecs, and Zapotecs. An Olmec inscription found in 2006 dates to between 1000 BC and 900 BC. That is 300 to 700 years before the Maya system first appeared in 300 BC. The Zapotecs of Monte Alban also developed a writing system prior to the Maya and the oldest examples of that writing date to 500 BC, or 200 years prior to the first Maya inscription.

Above: The Cascajal block is etched with the earliest known example of Olmec writing.

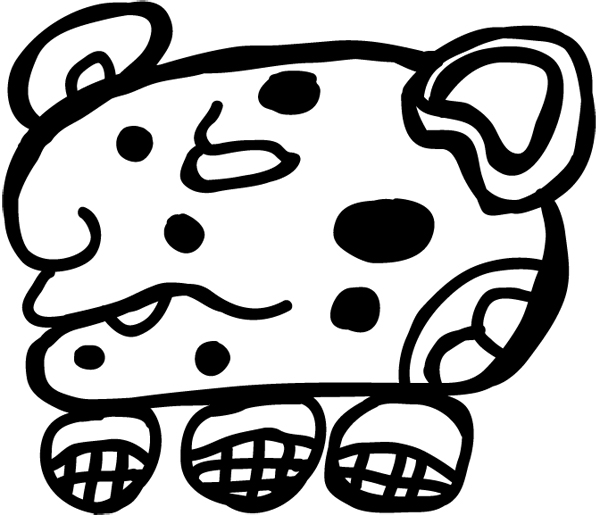

The Mayan writing system (often called hieroglyphs from a superficial resemblance to the Ancient Egyptian writing) was a combination of phonetic symbols (glyphs standing for sounds) and logograms (glyphs standing for concepts). This logo-syllabic writing system has more than a thousand different glyphs, although a few are variations of the same sign or meaning and many appear only rarely or are confined to particular localities. At any one time in history, no more than around 500 glyphs were in use. Around 200 of them (including variations) had a phonetic or syllabic interpretation.

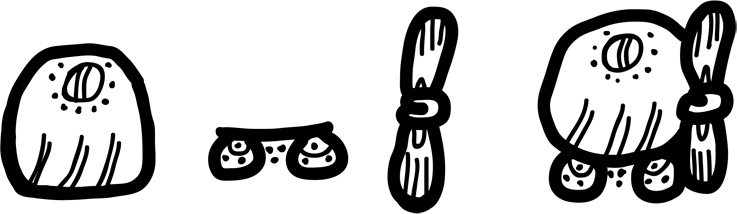

While one letter of our alphabet can represent only one sound, Maya writers could select from many different glyphs to represent the same sound. For example, there are at least five different glyphs that could be chosen to represent the syllable ba. However, the meaning of a given text also could be represented by a combination of glyphs which literally represent real objects or actions and which can also indicate adjectives, prepositions, plurals, and number, in addition to the phonetic glyphs which represent sounds.

Above: A representational glyph meaning “Balam” (tiger).

Above: Phonetic glyphs that read as “Balam” (tiger) when combined.

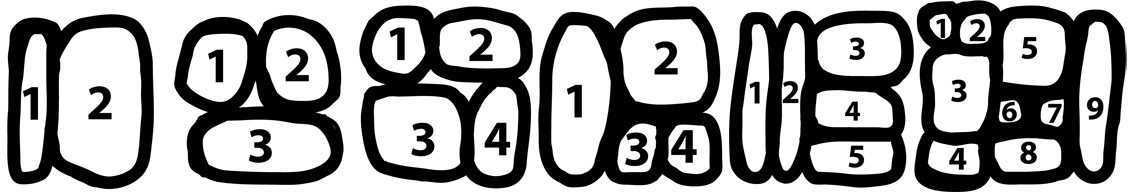

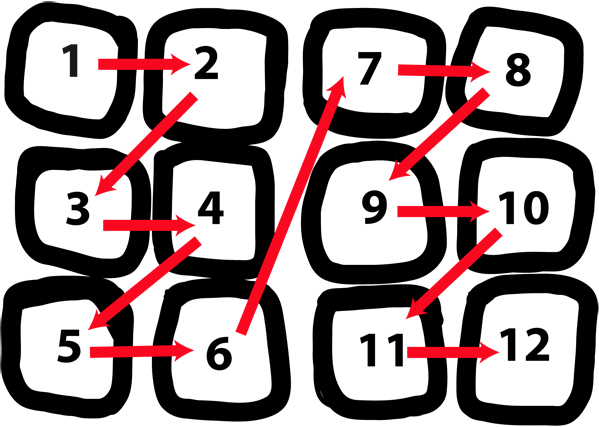

Above: Glyphs were arranged in blocks. The blocks of glyphs were read left to right, top to bottom. However, there are many different ways of constructing the block.

The blocks were placed in double columns. The text (made up of many blocks of glyphs) is read by starting from the top left, horizontally across two blocks, and then moving down to the nest row below. In very short texts the glyph blocks are placed in a single row and are read from top to bottom in vertical texts or left to right in horizontal texts. Sentences are structured verb-object-subject. Adverbs can be placed before the verb.

Above: Glyph text blocks are read left to right, top to bottom.

Example of Yucatec Maya (Màaya t’àan) translated into modern Latin text:Tuláakal wíinik ku síijil jáalk’ab yetel keet u tsiikul yetel Najmal Sijnalil.

English Translation: All men are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

Maya Numbering System

The Maya didn’t discover mathematics before anyone else, either; they adapted it from earlier Mesoamerican cultures, like the Olmec. For example, there are examples of Olmec dot/bar/glyph numbers dating from 650 BC, over 350 years prior to the earliest known Mayan glyph. The Epi-Olmecs also came up with the concept of “zero” long before the Maya.

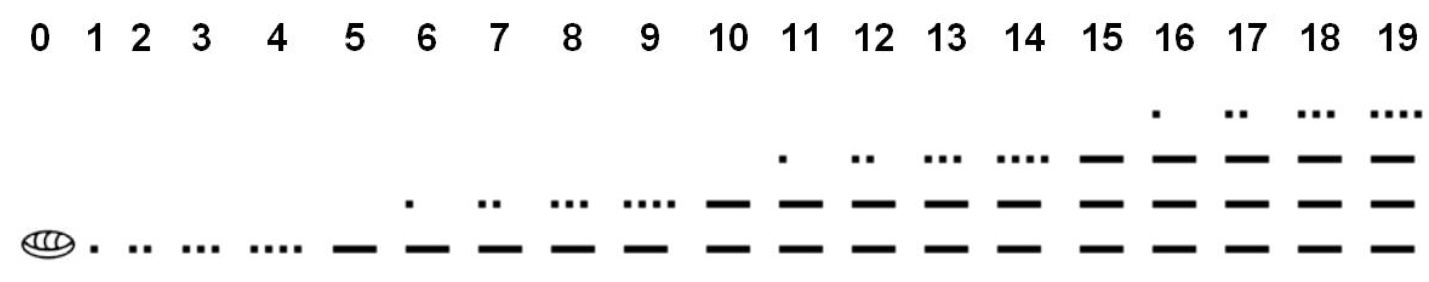

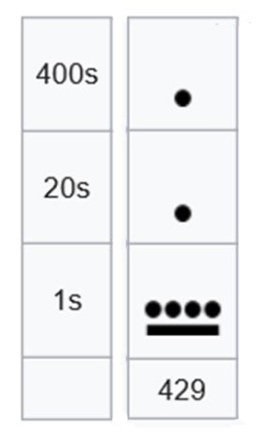

The Olmec/Maya numeral system is a vigesimal system, meaning it has a base of 20, unlike our system that has a base of 10. We apparently based our numbering system on counting on our fingers (base of ten). The Olmec and Maya, with their base of twenty, must have based theirs on counting on both their fingers and toes! The Olmec/Maya numerals are made up of three symbols; zero (a shell shape), one (a dot) and five (a bar). The symbols were arranged in a column, read from the top down.

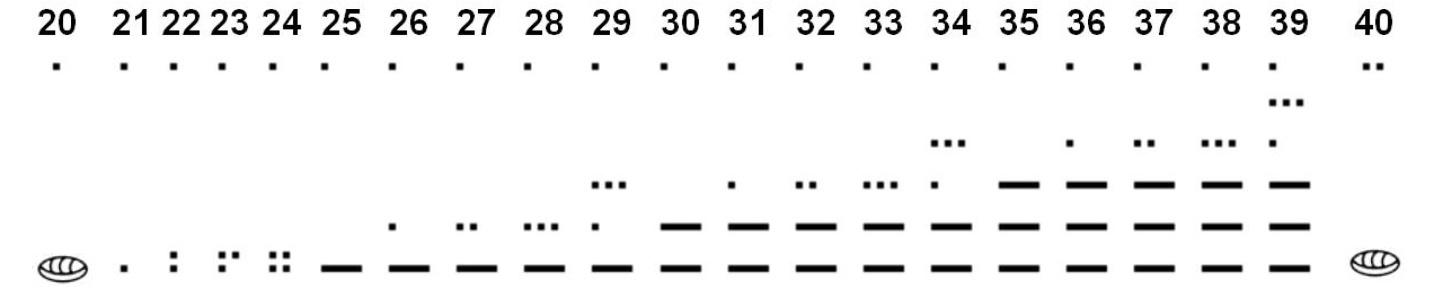

This system works up to nineteen, but rather than twenty being four bars, they started a new count above the first one. Numbers after 19 were written vertically in powers of twenty. Zero is represented by a shell. So, 20 is a single dot above a shell, 21 is a dot over a dot, 22 is a dot over 2 dots, and so on.

Thirty-three would be written as one dot (representing 20) above three dots (representing 3), which are in turn atop two bars (each representing 5).

When you get to 400 (or 202), another row is started on top of the stack. The number 429 is written with one dot above one dot above four dots and a bar, or (1×202) + (1×201) + 9 = 429.

The next level in the stack would be 8,000 (203 or 8000) and then 160,000 (204 or 160,000) and so on.

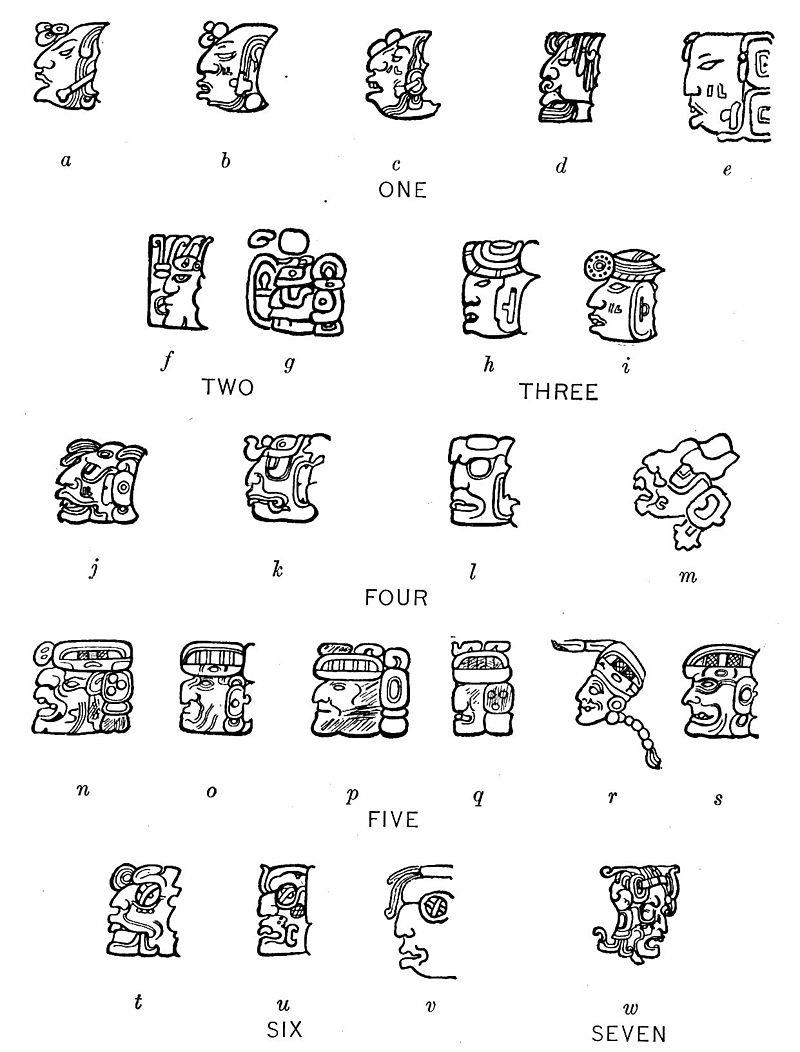

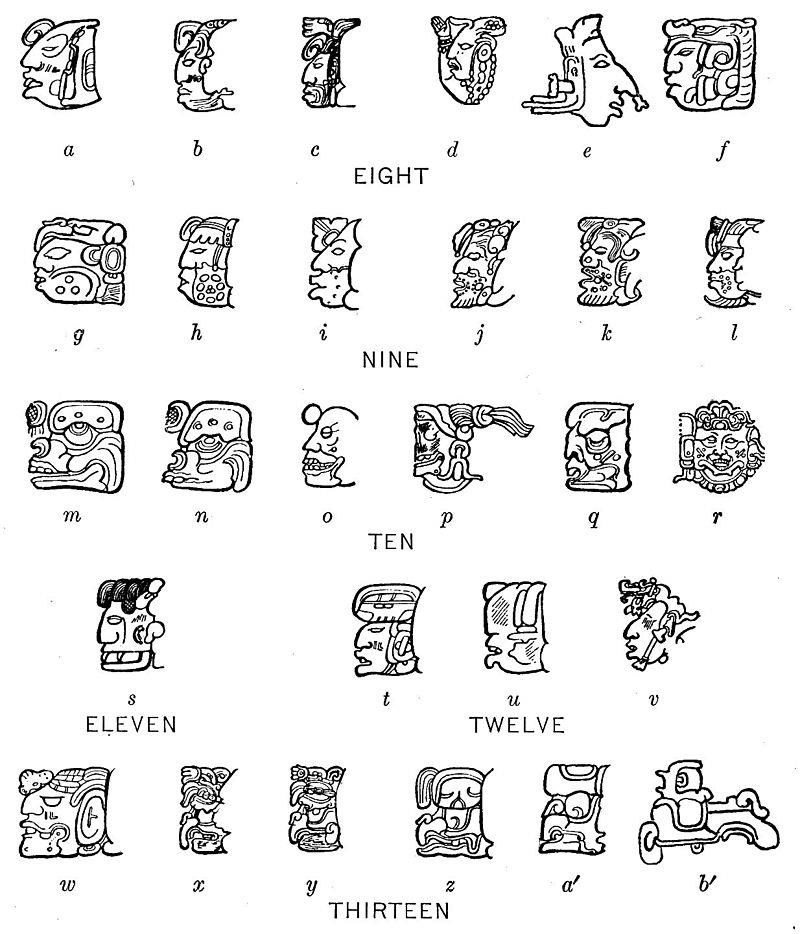

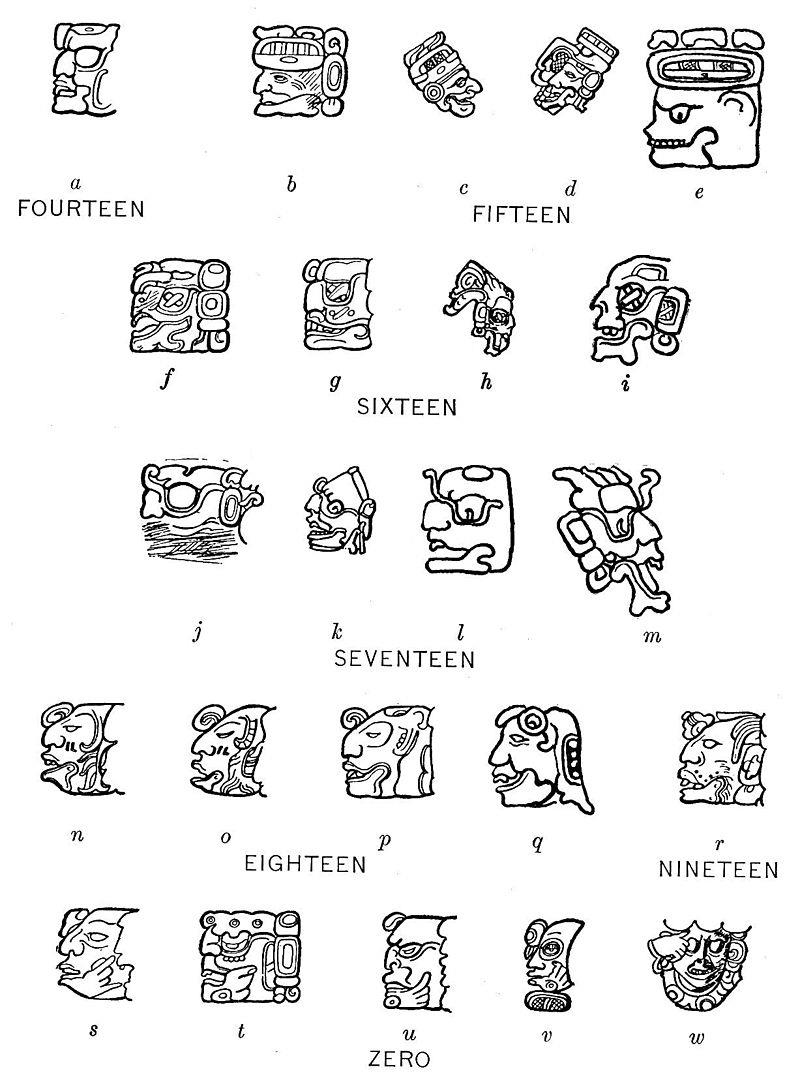

The Maya had a second number system, used for dating buildings and to use on calendars, etc. This would analogous to our practice of writing out a number in letters (nineteen) instead of digits (19) and was not used in calculations. This system contained the numbers 0 through 19. In this “head” notation each of the numerals, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13 is expressed by a drawing of a distinctive type of head; each type has its own essential characteristic, by means of which it can be distinguished from all of the others.

Above 13 and up to but not including 20, the head numerals are expressed by a unique characteristic of the head for 10 to the heads for 3 to 9, inclusive.

However, Mayan glyph writing was a highly individualized art form and each scribe had wide latitude on how he actually drew a particular glyph. It would be similar to the idea that if a drawing of a raccoon stood for the number 15, it didn’t really matter how you drew the raccoon, only that it would be recognized as one. Thus, there are an infinite number of ways to draw the same glyph that represents only one meaning.